“The black interior is a metaphysical space beyond the black public everyday toward power and wild imagination that black people ourselves know we possess but need to be reminded of. It is a space that black people ourselves have policed at various historical moments.

Tapping into this black imaginary helps us envision what we are not meant to envision: complex black selves, real and enactable black power, rampant and unfetishized black beauty.”

– Elizabeth Alexander, The Black Interior

Black Interiors:

Envisioning a Place of Our Own

In her seminal text The Black Interior, Elizabeth Alexander describes a reality beyond what is currently perceptible to the senses. One constructed and cultivated by black people away from the scrutiny of those who try to invade and dictate both the physical and spiritual domains of their existence. Pulling inspiration from Alexander’s collection of essays, Black Interiors: Envisioning a Place of Our Own explores the black aesthetic and psyche by drawing attention to interior spaces as sites of liberation and creative expression.

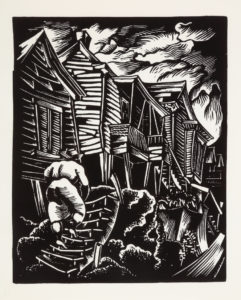

Behind the façades of Loïs Mailou Jones’s “Old House Near Frederick Virginia” (1942) or the southern “shacks” which inspired Beverly Buchanan’s “Untitled (Red Ladder)” (1995) are domestic spaces that are nurtured and protected. Within these enclosed walls African Americans re-envision space as freedom, fashioning their homes to reflect their personal values and cultural memory. The interior of the home—along with all who dwell within—is sacred for African Americans, who have consistently wrestled with the impermanence of place perpetrated by chattel slavery, Jim Crow, and gentrification.

This exhibition showcases artwork as well as archival documents including: photographs, correspondence, memorabilia, and newspaper articles related to the continuous efforts of those within the African Diaspora to designate and create communities of their own within the United States and abroad. Artists from Clark Atlanta University Art Museum and Spelman College Museum of Fine Art’s permanent collections offer a glimpse into private rooms of the home to depict precious moments of solitude and contemplation, while personal letters, family photos, and diary entries collected and preserved by the Atlanta University Center Archives Research Center disclose intimate details of life as an African American. By unpacking the politics and poetics of the often racialized and gendered space within and around the household, the works included critically examine how our social relations and cultural practices are shaped.

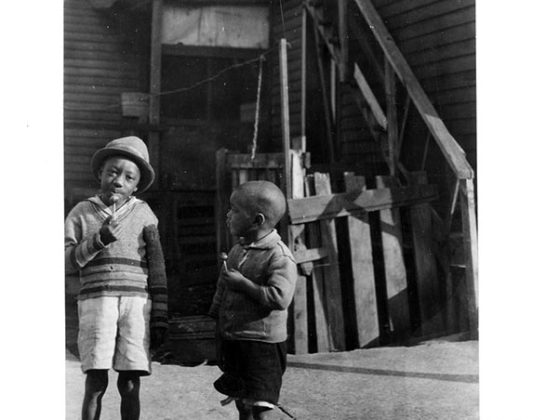

William Anderson

Playing in the Ghetto-Savannah, GA, 1972

Gelatin Silver Print, Archival Process

AUC Woodruff Library

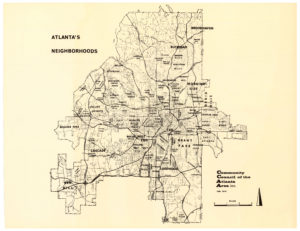

For decades the “American Dream” of individual wealth and success has symbolically been linked to the ability to purchase and own a house with a private yard surrounded by a white picket fence. However, homeownership for African Americans had been a dream deferred and outright denied until 1868. Even after the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment — which granted African Americans’ citizenship and forbid any state from depriving “any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law” — other regulations were established, such as Black Codes and Jim Crow laws, to restrict and control the movements of African Americans. Gerrymandering, redlining, and gentrification are contemporary tactics still used by the state to reinforce forms of inequality and maintain racially-contingent forms of property and property rights.

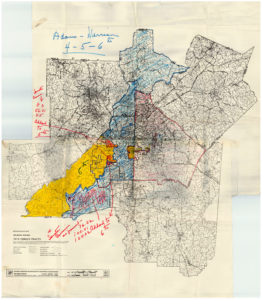

Even with such systematic forms of oppression upheld by the local and federal government, African Americans have continued to design their own homes, develop sustainable neighborhoods, and counteract discrimination through elected office. These efforts include: University Homes, the first federally subsidized housing project for black residents in the United States, the Herndon Home, a fifteen-room mansion designed by professor and activist Adrienne Herndon, and Grace Towns Hamilton’s work to redistrict the 5th and 6th districts of Atlanta to increase black congressional representation. Throughout the 1900s, various legislation was passed in an effort to focus on the housing issues for low income people and African Americans, including the Housing Act of 1937 for public housing projects and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 for the outlawing of discrimination in housing and in mortgage lending. Additionally, in 1992, the HOPE VI urban-revitalization demonstration program authorized by Congress provided grants for mixed-income housing.

With the passage of such laws, African Americans still struggled to achieve equality in housing. To this day, major cities in the United States have neighborhoods that are racially and economically segregated.

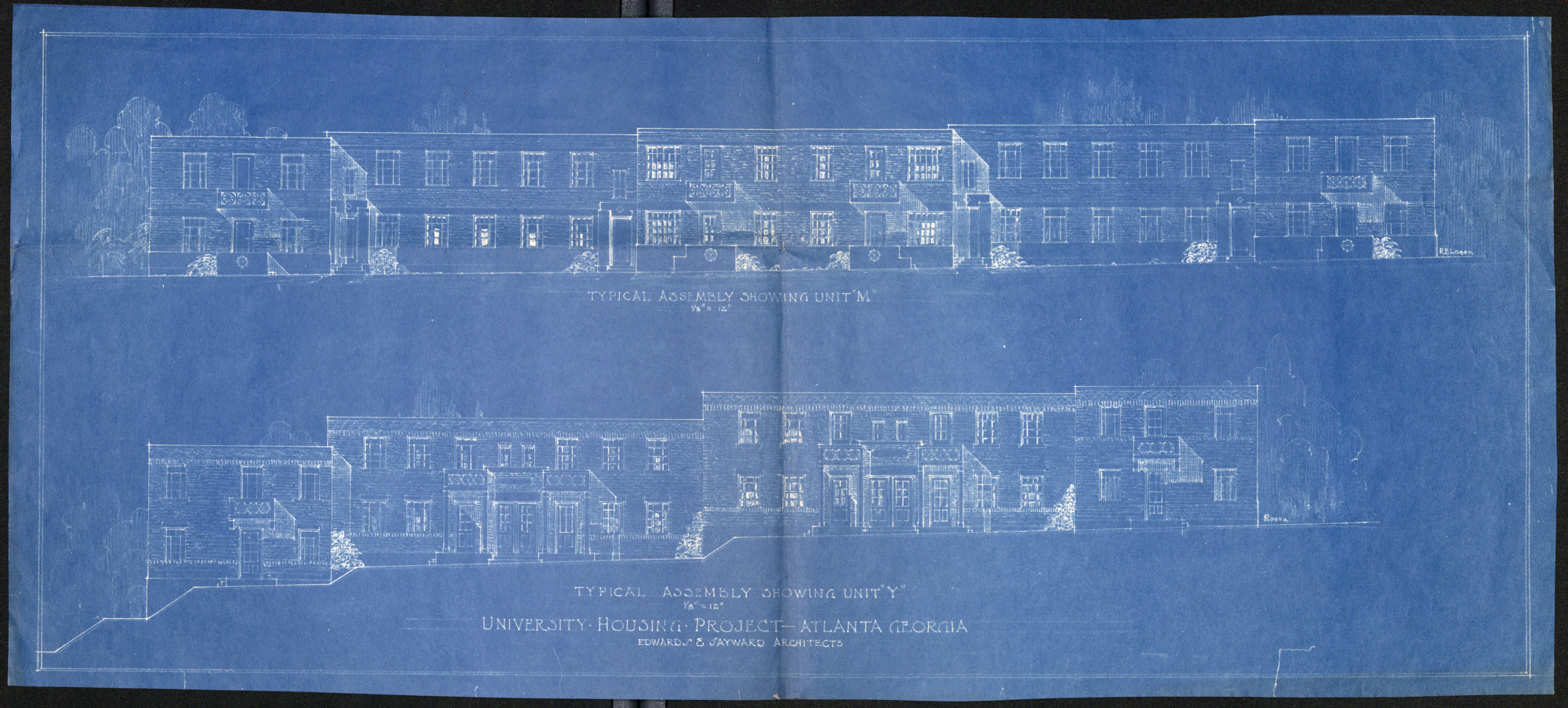

University Housing Project, Atlanta, GA (Typical Assembly Show Unit “Y”)

John Hope

undated

Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library

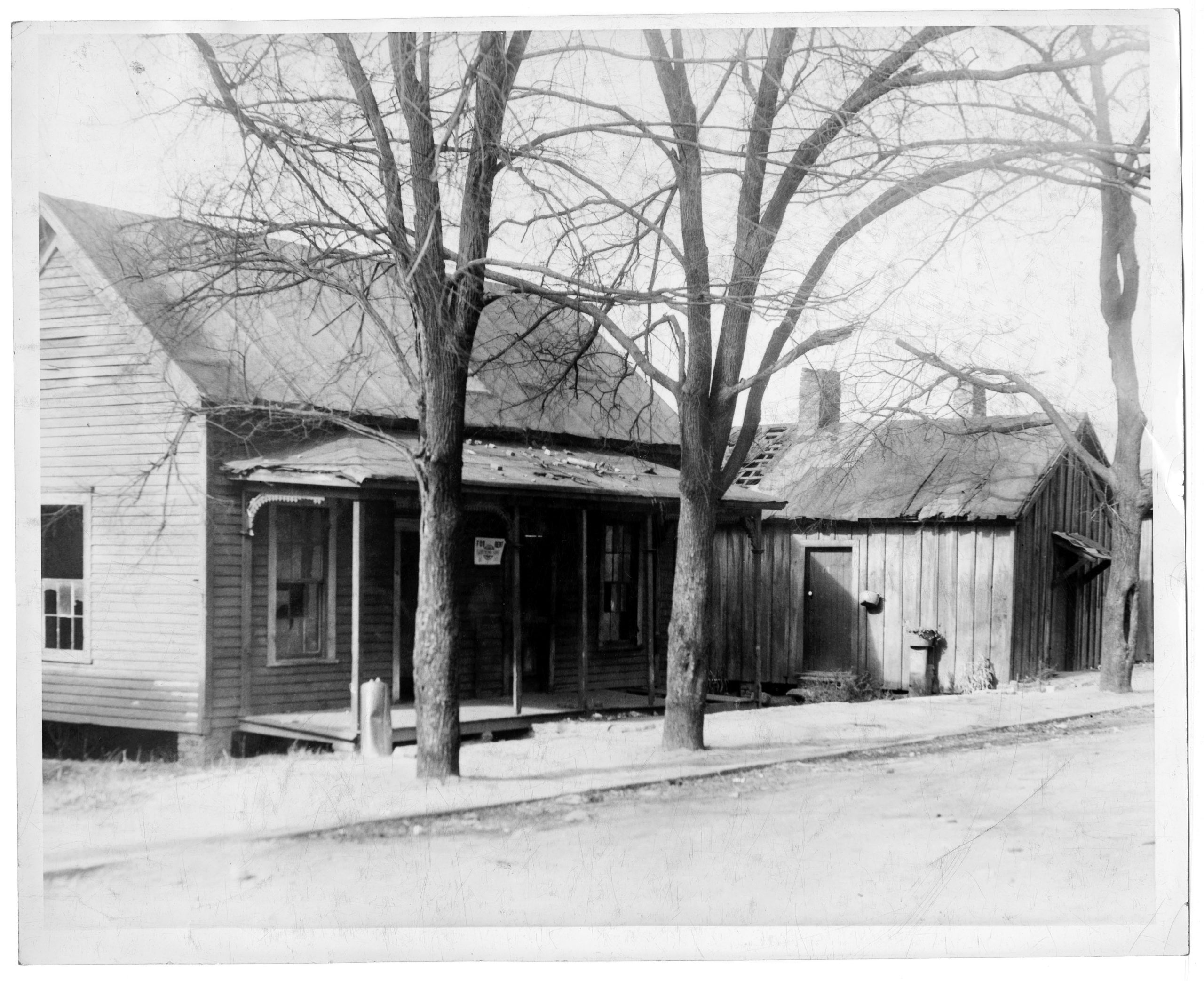

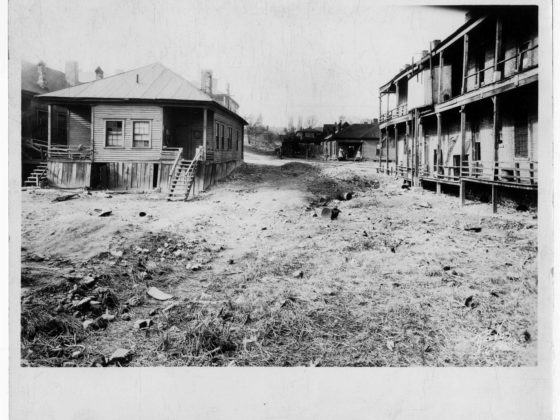

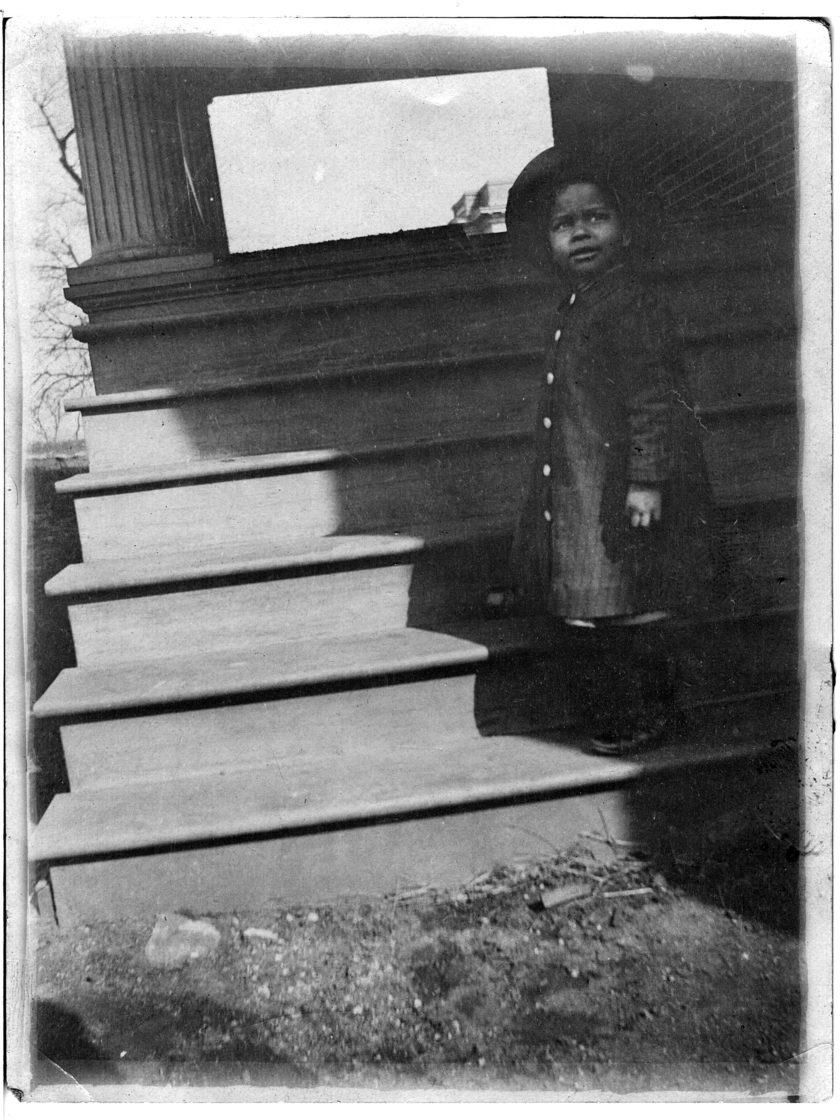

University Homes was the first federally subsidized housing projects for African Americans. Built between 1935 and 1938, it was located in the former Beaver Slide slums near Atlanta University. This housing project was the African American counterpart to Techwood homes, the first federal housing project built near what is the present-day campus of Georgia Institute of Technology. Housing projects like University Homes were built in the 1930s as a way to provide affordable housing to low income families by erasing slums from the city. These slums were mostly home to African Americans living in Atlanta, impoverished by Jim Crow laws and segregation.

University Homes was the product of John Hope’s desire to improve the surrounding neighborhoods of the Atlanta University Center and have a public housing project near the campuses to rid it of blight and despair. John Hope served as the first African American president of Morehouse College and Atlanta University. During his life he supported public education, adequate housing, health care, and job opportunities for African Americans. Through his work, University Homes was created, as well as a community for African Americans. However, this project did not provide housing for the most impoverished of the Beaver Slide slum. Those displaced by the public housing project were unable to afford the rents to continue to live in the area. The area would eventually become an impoverished area for African Americans again, and, like the other housing projects in Atlanta, it was demolished in the 2000s.

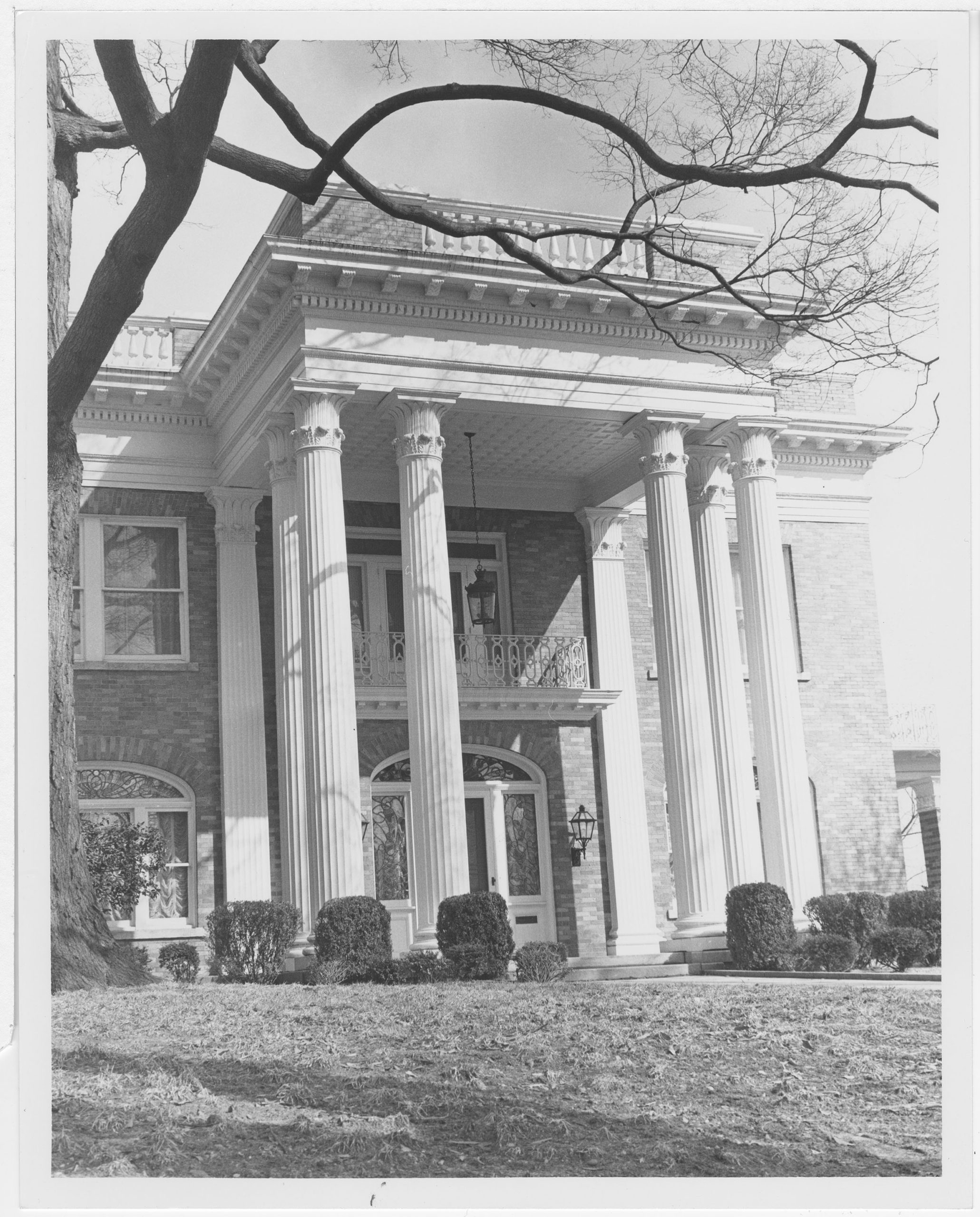

Several decades before the completion of University Homes, another influential man broke ground in a neighboring community close to Atlanta University to build a home of his own. The Herndon Home was the residence of entrepreneur Alonzo Herndon. Born into slavery, Herndon would go on to become Atlanta’s first black millionaire. He owned several barbershops throughout the city and was the founder and president of the Atlanta Life Insurance Company. Unlike Hope’s modest University Homes, Alonzo Herndon’s two-story, fifteen room mansion was a public declaration of his prosperity and wife’s artistic expression. The home was built as a statement of his wealth and position in African American society in the early 20th century.

Designed by Herndon’s wife, Adrienne, the house was mostly constructed by African American craftsmen. It showcases different popular design styles for mansions on the interior and exterior. The home and family represented the black elite and showcased the development of black businesses, education, and culture happening in Atlanta in the 1900s, illustrating the family’s aspirations and lifestyle.

The neighborhood surrounding the home was once a thriving African American middle-class community, notably resided in by the Towns family: including patriarch and Atlanta University professor George A. Towns, as well as his daughter, Grace, who would grow up to be the first African American woman elected to the Georgia General Assembly as representative for Vine City. However, in the 1970s, the Vine City neighborhood deteriorated into a corner of poverty, and with it, the area surrounding the mansion. The Herndon Home opened as a museum in 1983 and was designated as a National Landmark in 2000. Today, it stands in contrast to the surrounding homes that are abandoned and boarded up.

Alonzo Herndon Home

circa 1915

Morris Brown College Photographs

Click on the arrows in the viewer to page through the booklet or expand to full screen to see a larger version.

Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000) poignantly illustrates the interconnectedness of race, gender, class, and architecture in his 1958 painting, “Brownstones.” With short, fine brush stokes, Lawrence orchestrates the rhythmic commotion of a busy city street and creates meaningful spatial relationships between each simplified figure to convey their physical proximity as well as their communal ties. Lawrence visually records the inner workings of a community through this painting by blurring the lines between the public and private spheres. In an almost voyeuristic fashion, we can peek through each tenant’s windows and open doorways to see who they are and how they live.

While much detail goes into depicting the social interactions between the residents of the three neighboring brownstones, just as much emphasis is given to the actual dwellings themselves. In fact, the physical structure of the homes inform the ways in which residents move and engage with one another. The stoop, doorway, and sidewalk are all gathering places for the tenants highlighting the intrinsic impact the built infrastructure has on the social structure of a community. With the heavy influx of African Americans from rural southern cities to urban metropolises in the Northeast, Midwest, and West during the Great Migration, many rowhomes were converted into multi-family units with overcrowded and cramped living conditions. Even with small living quarters, residents found creative ways to transform their domestic spaces into places that were reflective of their lifestyles, aesthetics, and true selves.

The front porch, along with the abovementioned white picket fence, has been an architectural fixture in American life. But unlike the fence which keeps outsiders at bay, the porch and stoop act as an extension of the interior space of the home to welcome community members as a place to gather and join in fellowship.

- Describe how practices like redlining lead to neighborhoods that are still segregated to this day. Come up with additional examples of other methods and practices that perpetuated segregated neighborhoods.

- What impact did the Great Migration have on black culture, as well as popular culture?

- Click here, for more information on the cultural significance of the front porch.

- For more research questions and additional sources, check out our LibGuide!

“Freedom Concept”

circa 1965

Johnson Publishing Company clipping files collection

AUC Woodruff Library

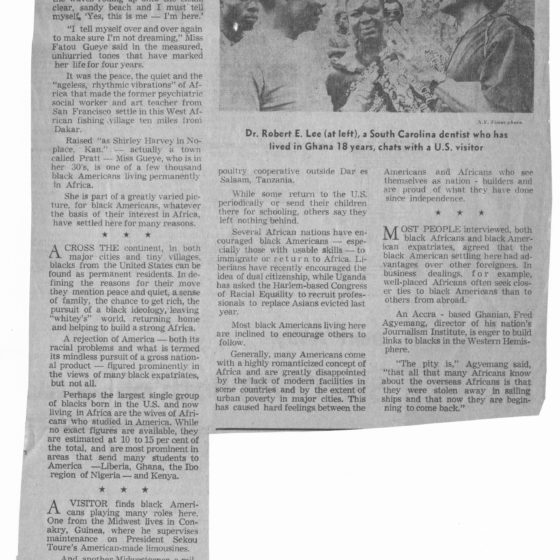

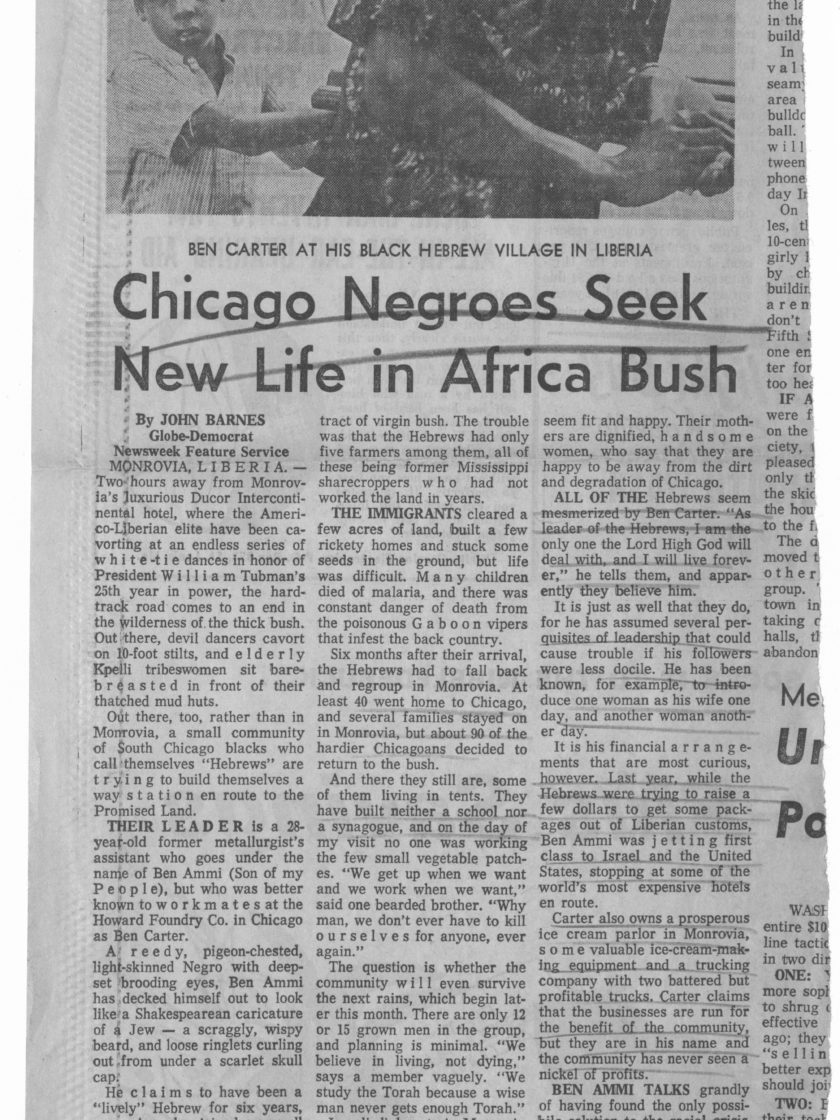

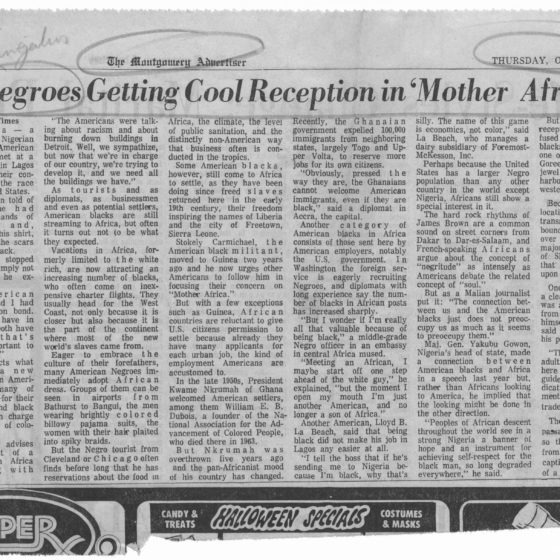

Journalist Thomas H. Johnson describes in his New York Times article, “Black on Black,” the experiences of African Americans moving abroad to African countries:

“Across the continent, in both major cities and tiny villages, blacks from the United States can be found as permanent residents. In defining the reasons for their move they mention peace and quiet, a sense of family, the chance to get rich, the pursuit of black ideology, leaving ‘whitey’s’ world, returning home and helping build a strong Africa.”

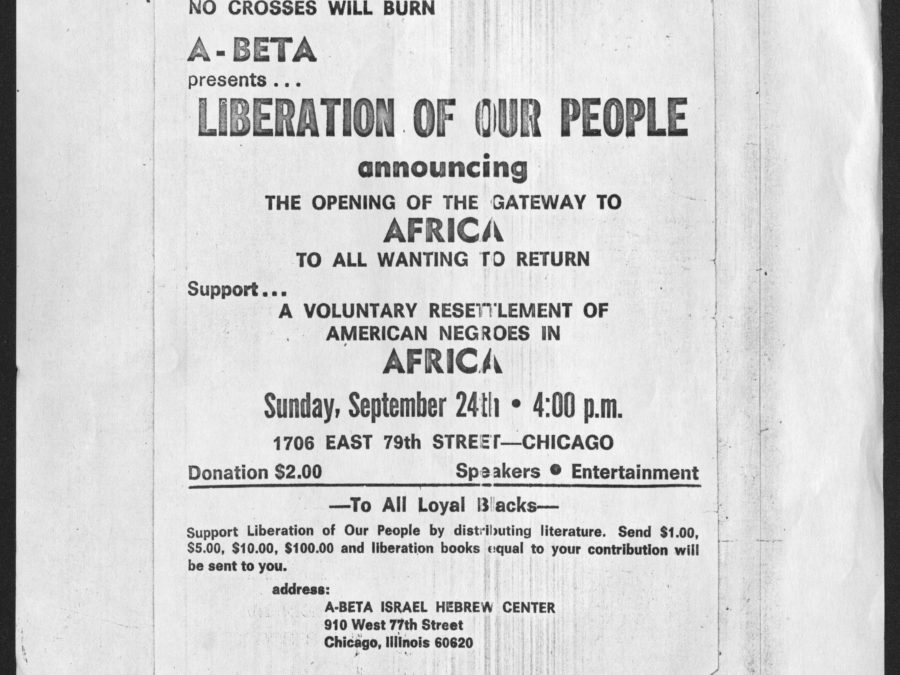

While the reasons differed from person to person, many African Americans desired to permanently relocate to African countries during the 19th and 20th century. The “Back to Africa” movement, which originated in the United States during the 19th century, spurred this desire by encouraging blacks to “return” to the continent their ancestors were taken from, due to transatlantic slave trade. The British colony of Sierra Leone, a free settlement for black people throughout the African diaspora which had remained loyal to the British during the Revolutionary War, would serve as a model for the settlement of Liberia in 1821 by the American Colonization Society (ACS). Prior to the settlement of Liberia, Paul Cuffe, a black merchant from New England, brought 38 settlers to Sierra Leone in 1816, marking the first formal migration of African Americans to Africa. Though ACS later assisted in the emigration of thousands of African Americans to Liberia, for the most part, the organization was opposed by African Americans who viewed ACS’s goal “as a means to get rid of them,” (Blyden, 2004).

The movement began to lose steam until the Reconstruction era when conditions throughout the United States, particularly in the South, forced African Americans to, yet again, reexamine their place in American society. This reexamination coincided with the rise of Marcus Garvey and his creation of the Black Star Line in 1919 to facilitate the transfer of African Americans globally. Scandal, and Garvey’s eventual arrest for mail fraud, plagued the Black Star Line, which was ultimately a failure. Despite the scandal, Garvey is still considered to be one of the forefathers of Pan-Africanism, the ideology that people of African descent share common interests and should be unified. Pan-Africanism, as espoused by Garvey and W.E.B. Dubois, served as a pre-cursor to the black nationalism movement that arose from civil rights activism in the 1960s and 1970s. The late 1960s even saw the introduction of legislation for the United States government to provide land and transportation for African Americans to settle in Africa. However, the so-called “Back to Africa” bill was opposed by African American members of Congress, including the bill’s sponsor, Representative Robert Nix of Philadelphia, who sponsored the bill at the request of a constituent.

Despite the ideals of Pan-Africanism, many of those who emigrated to Africa over the years found re-settlement difficult. While many felt connected by a common identity, the original settlers of Britain’s Sierra Leone, comprised of “various African ethnicities and multicultural New World black populations…turned out to be a site of friction and racial tension with its inhabitants exhibiting unexpected individuality and independence” (Blyden, 2004). In 1968, Ben Carter, leader of the fringe group known as the African Hebrew Israelites, led a contingent of African Americans to settle in Liberia. The group was met with resistance from the Liberian government, and many returned to the United States, disappointed.

To learn more about Marcus Garvey, make an appointment with the AUC Archives Research Center to view our microfilm collection of Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association records

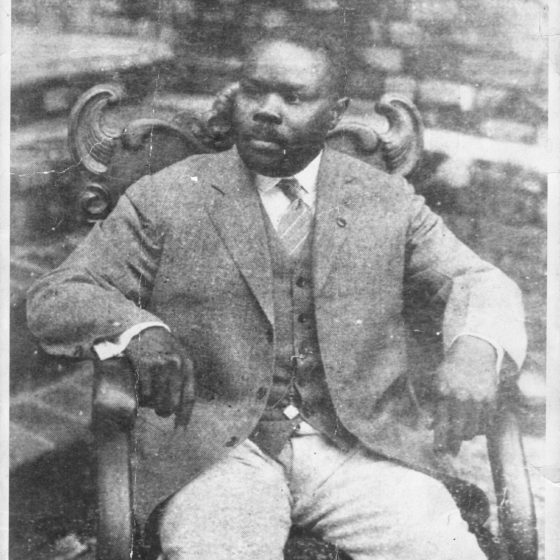

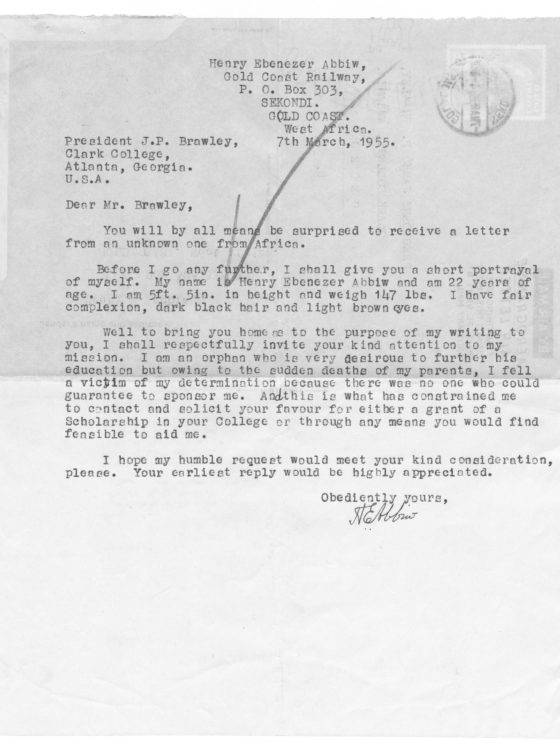

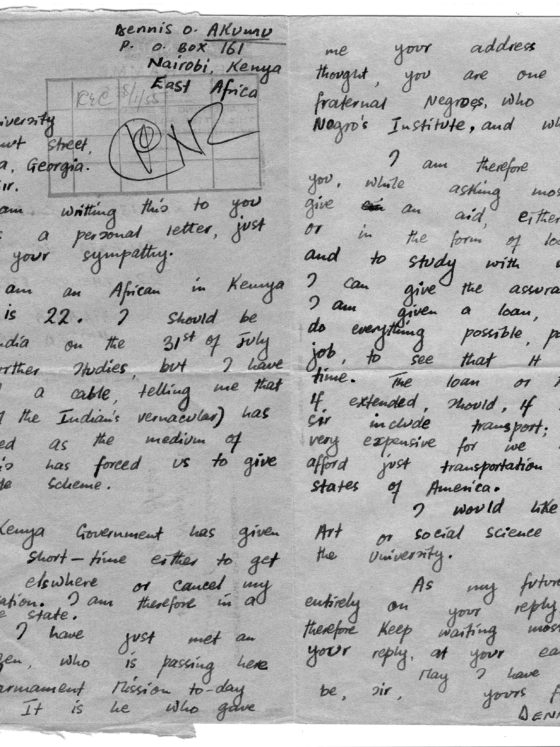

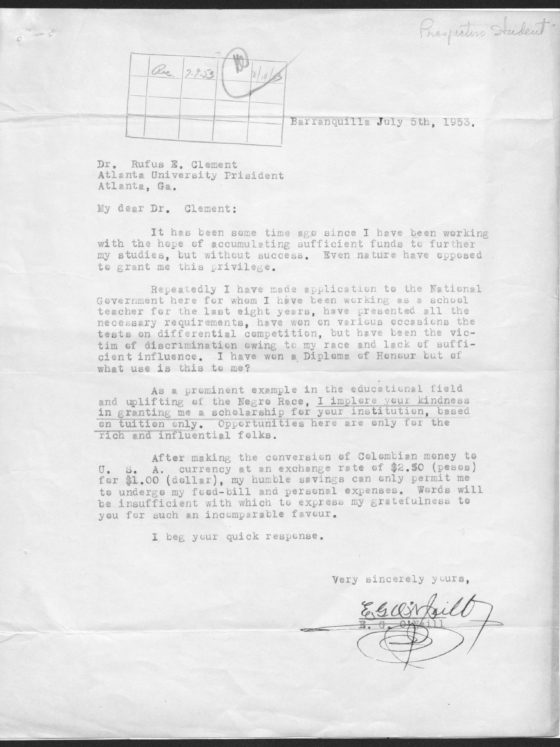

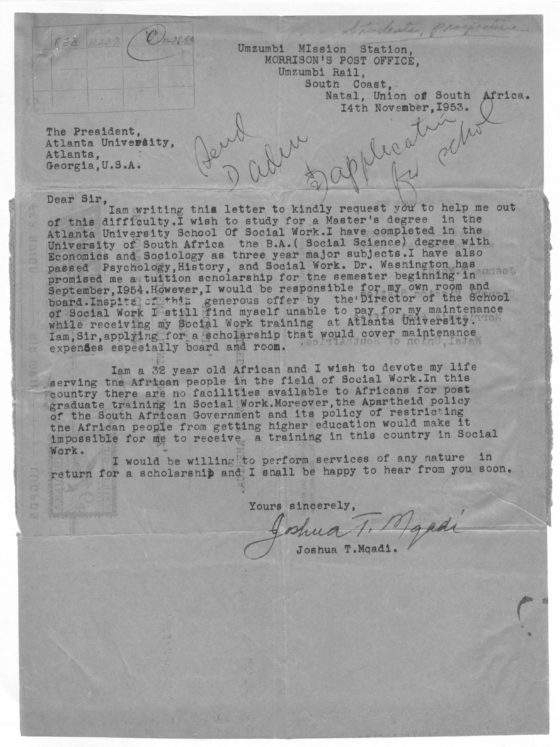

James P. Brawley

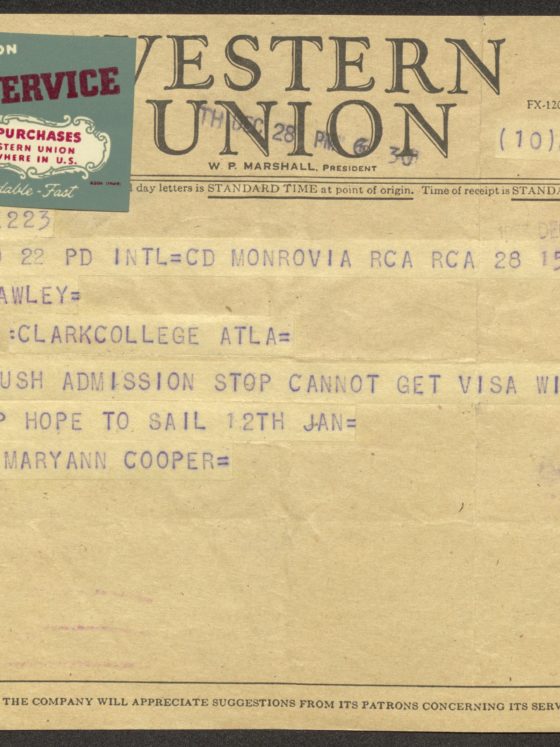

Maryann Cooper Telegram, circa 1940

AUC Woodruff Library

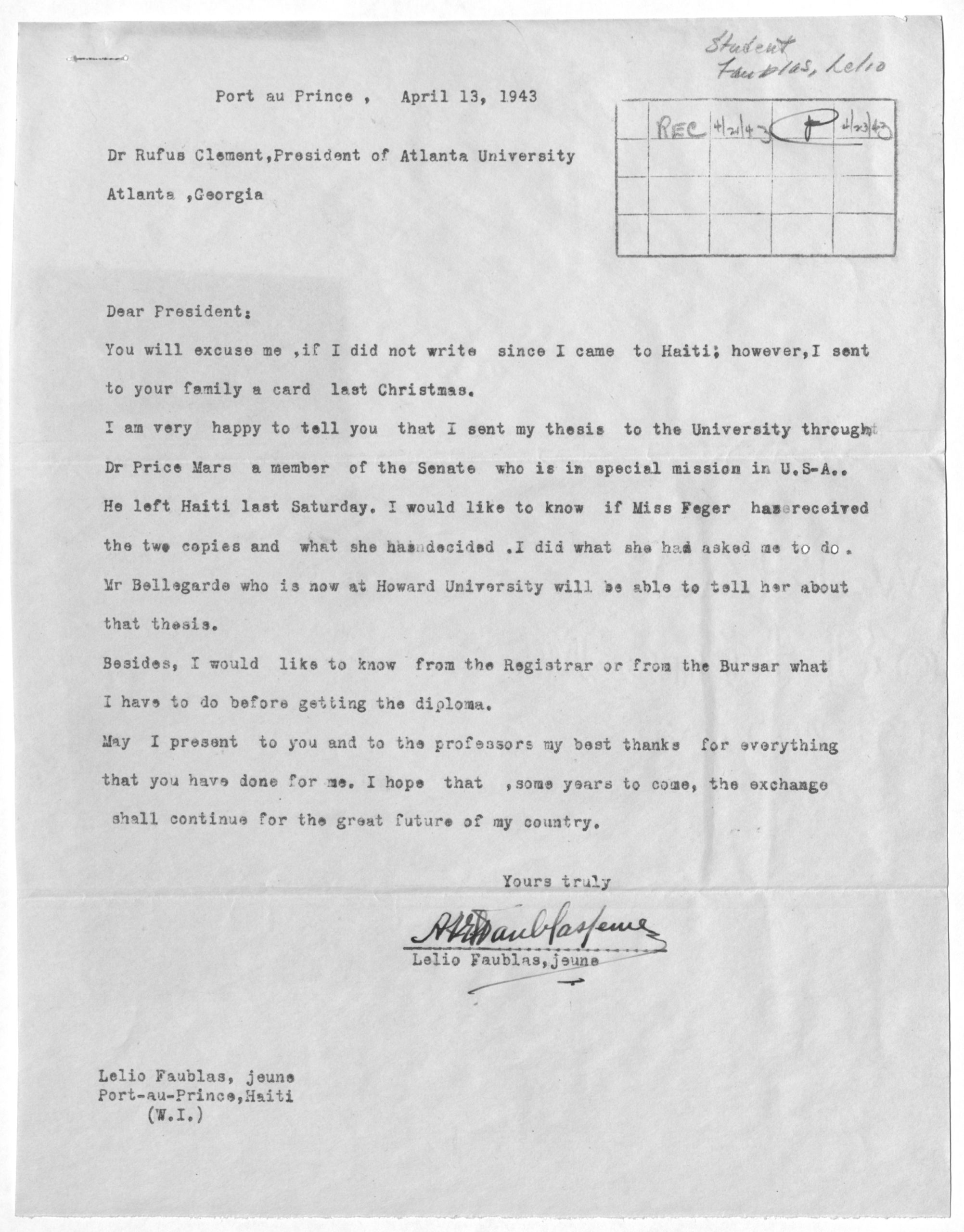

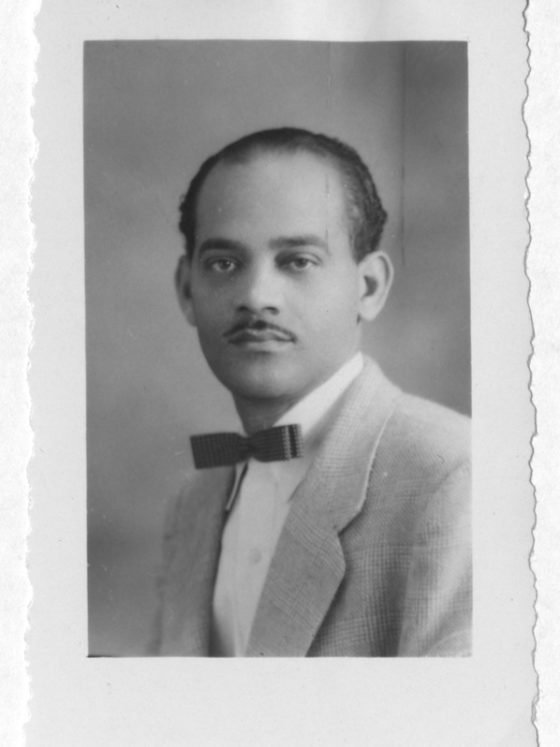

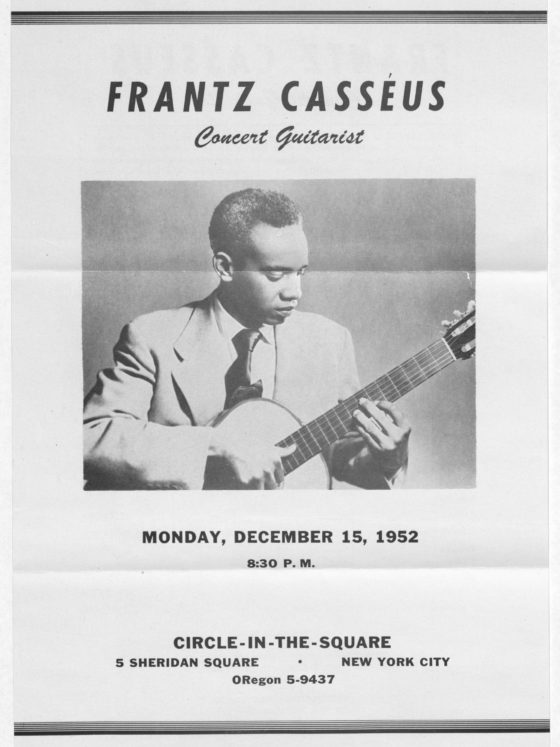

The cultural exchange between Africans and African Americans was far from one sided. In fact, African and Caribbean students wished to travel abroad as well to further their education and flee colonial rule. One such student was Lélio Faublas Jeune of Haiti who came to Atlanta University in 1940 to study education as an exchange student. Once he returned home he assisted in putting an end to Haiti’s prohibition of the use of Creole in education. (Péan, 2013). A sample of Faubla’s writing from around the time he studied at AU is available on JSTOR.

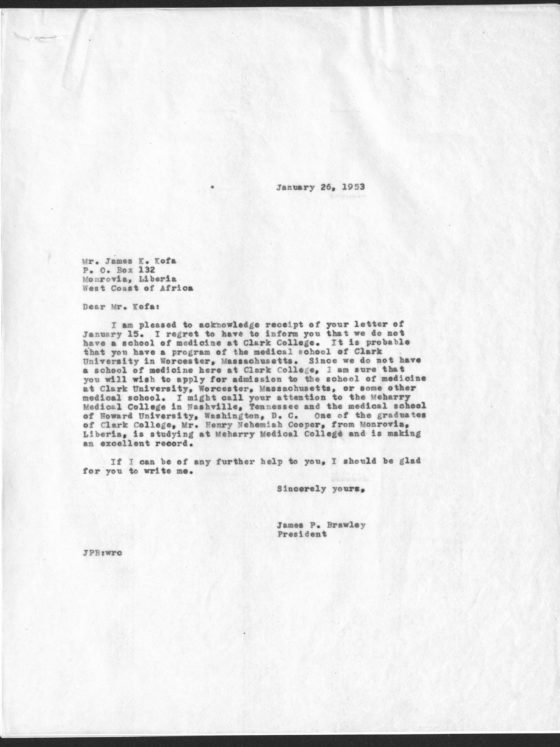

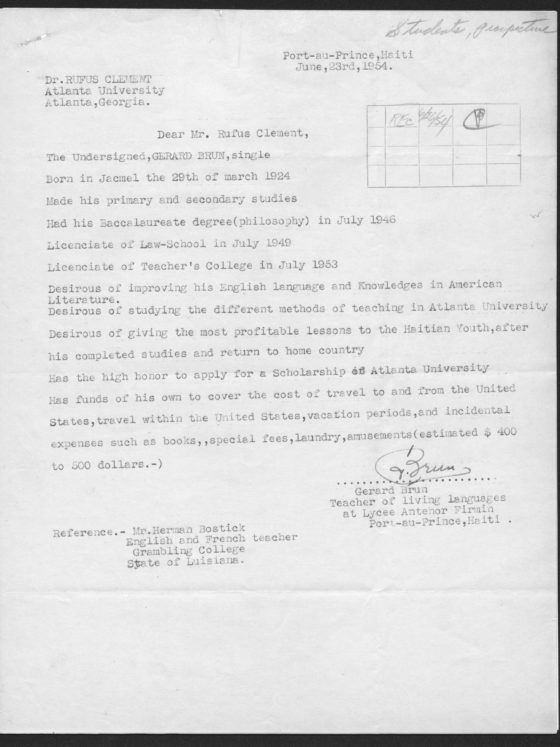

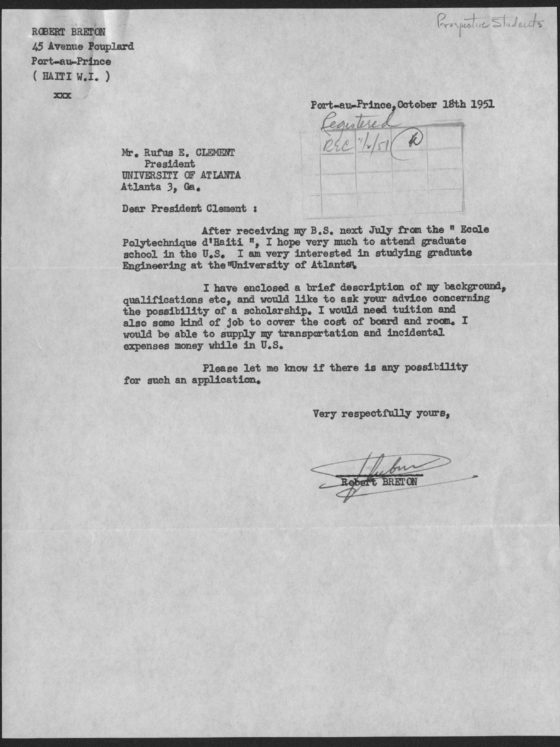

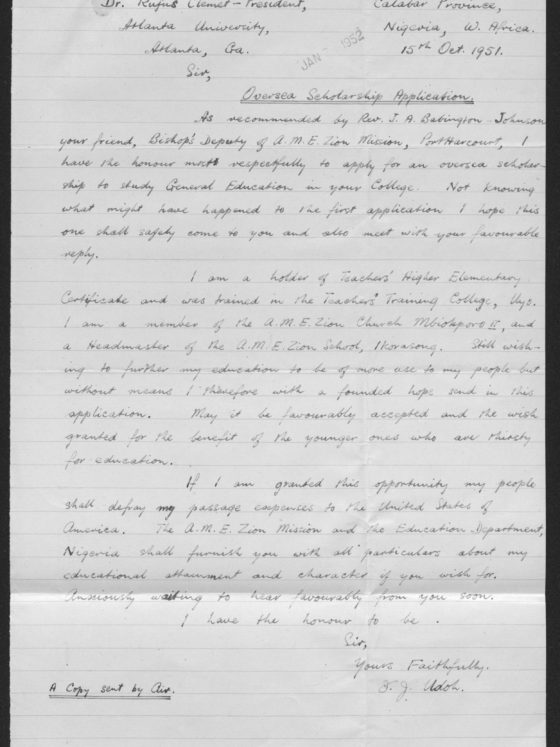

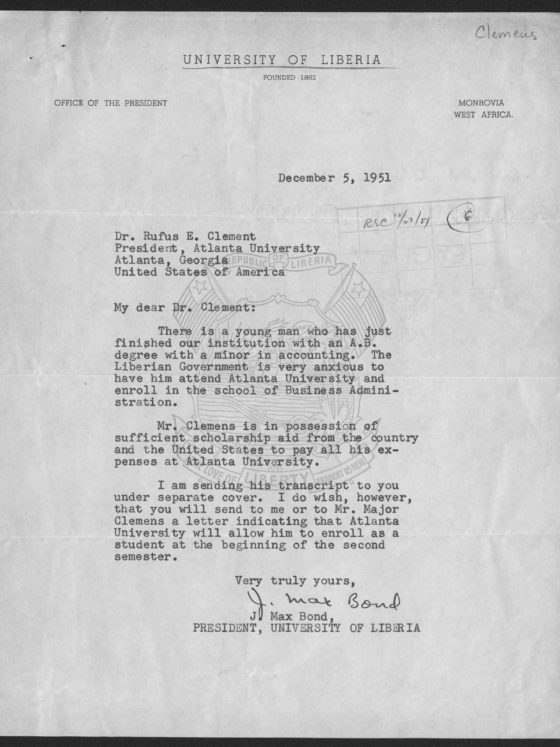

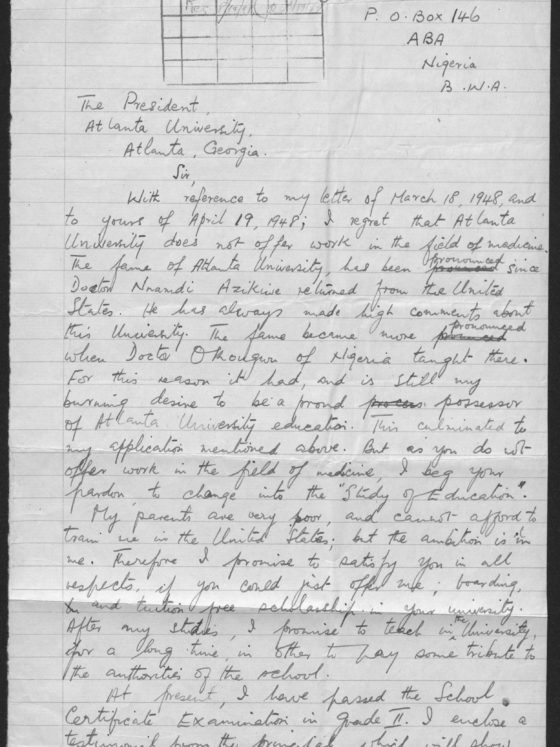

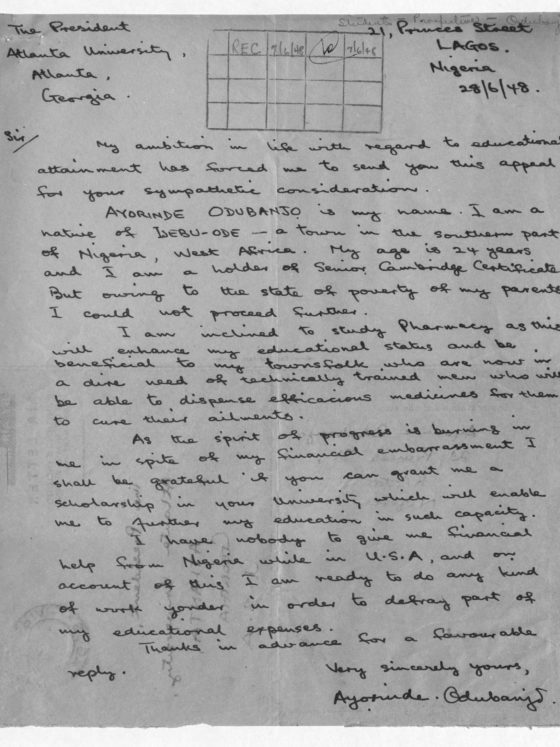

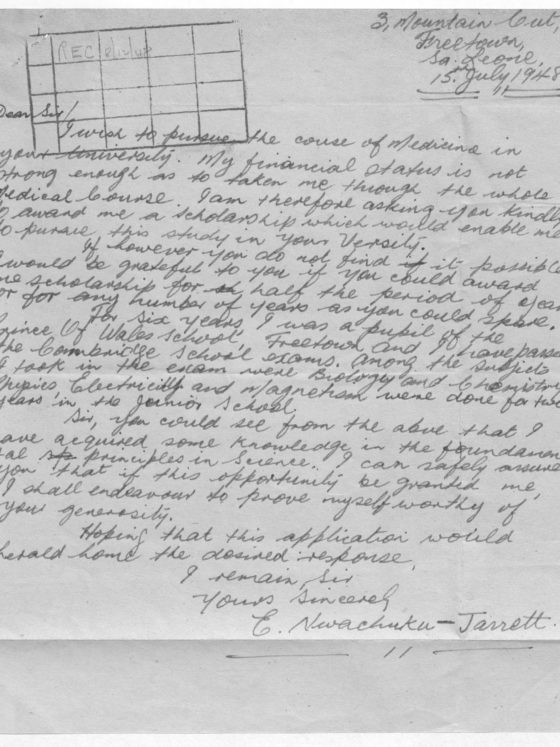

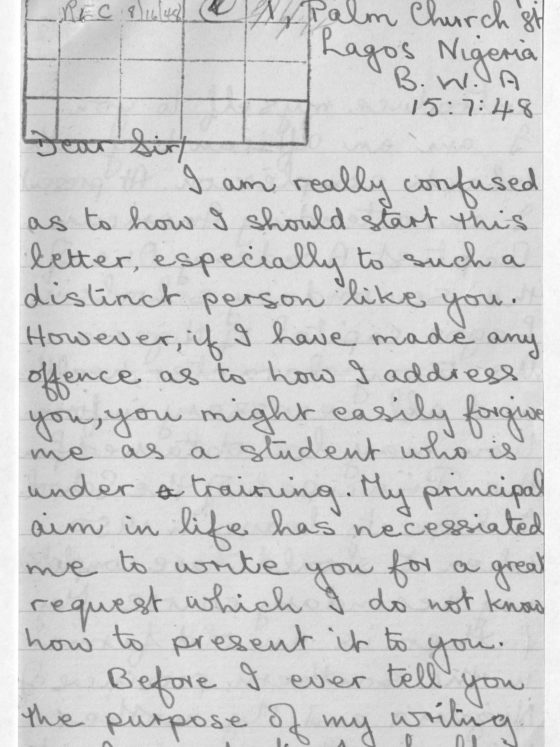

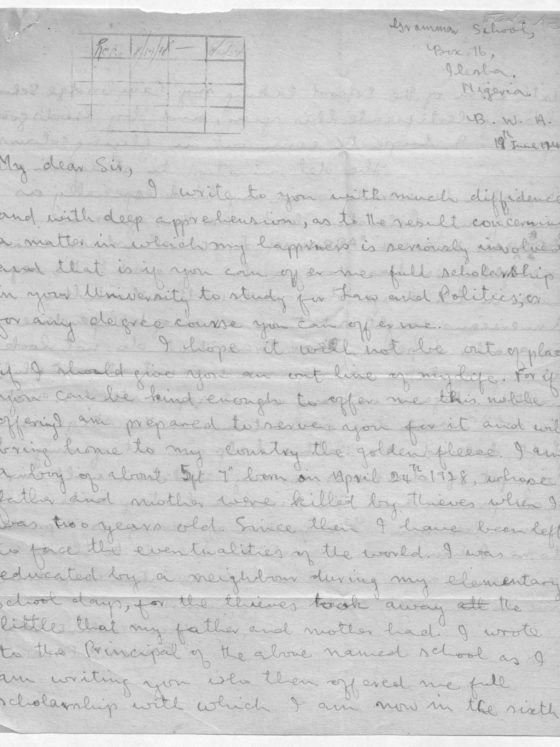

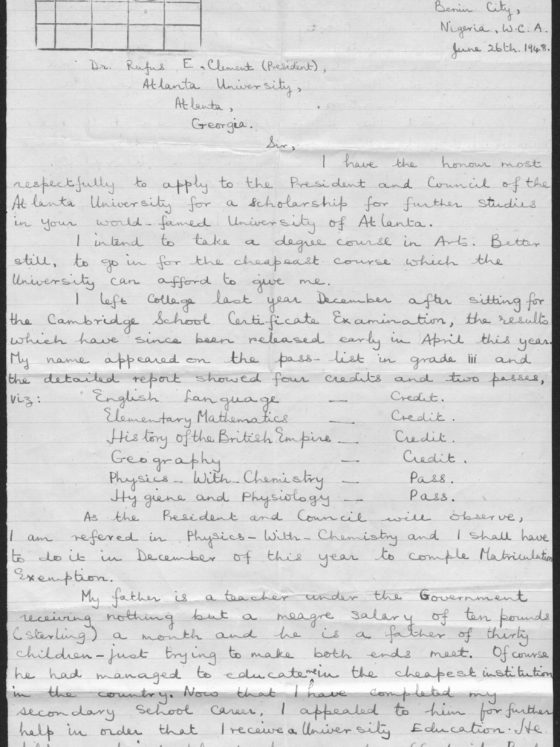

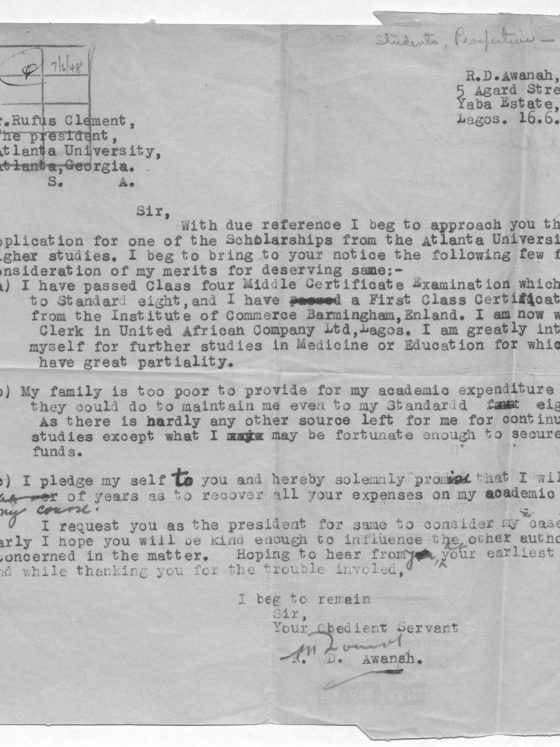

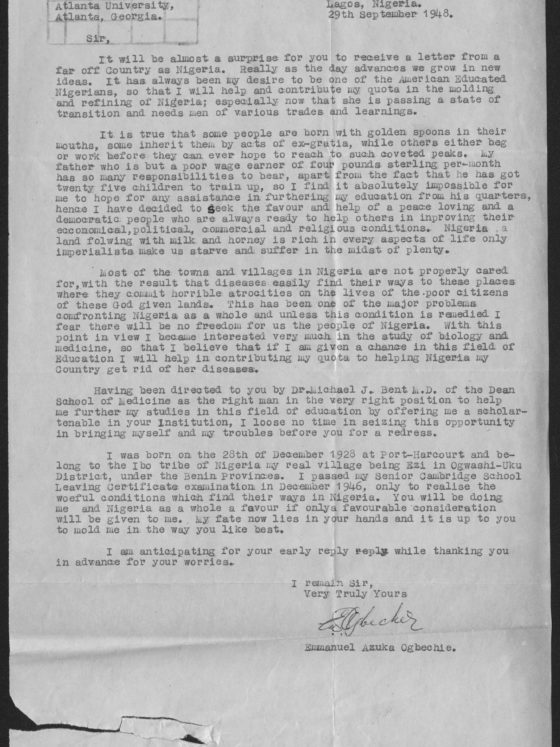

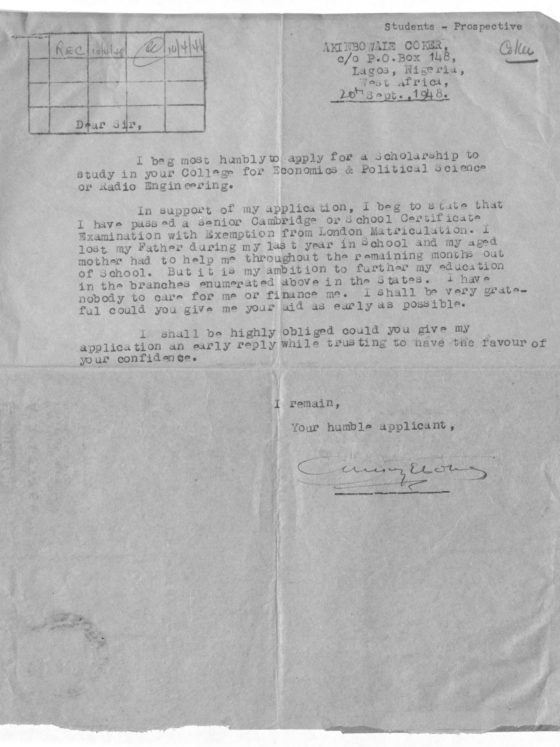

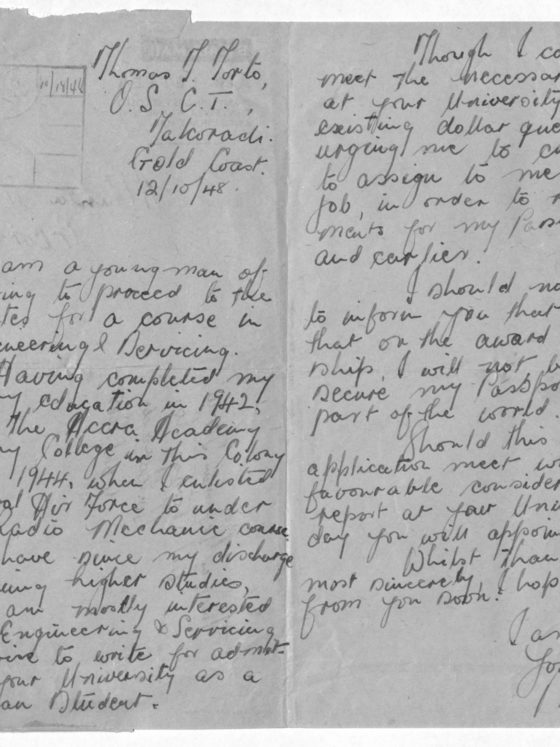

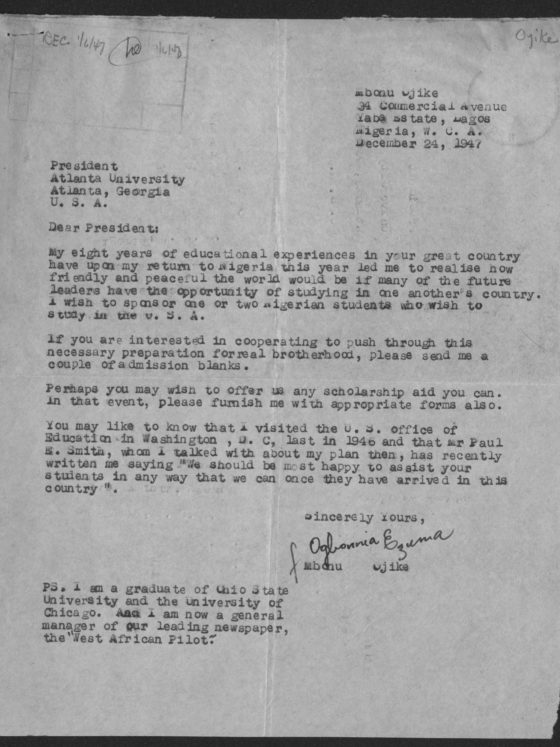

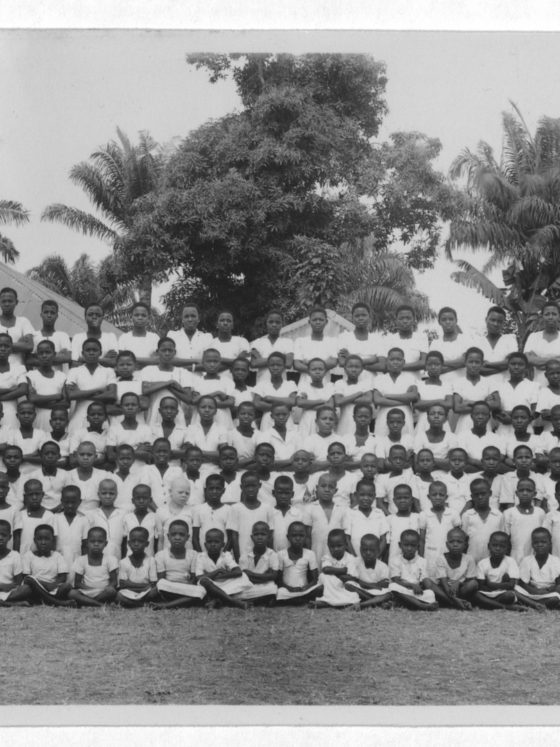

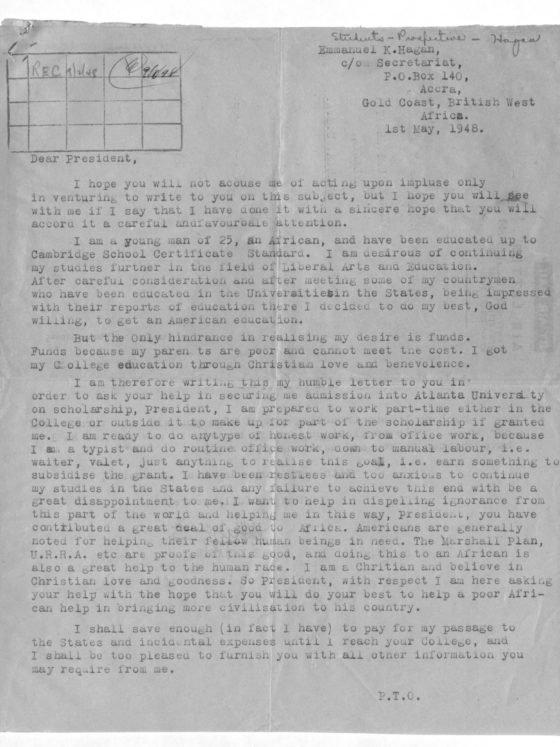

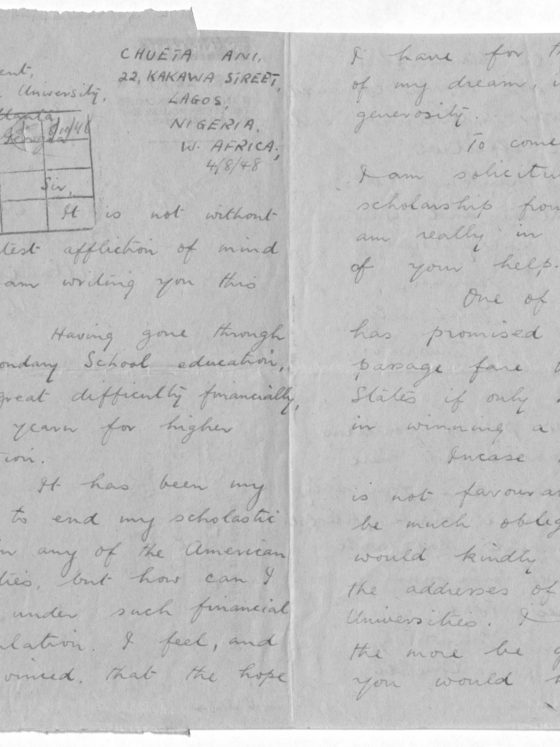

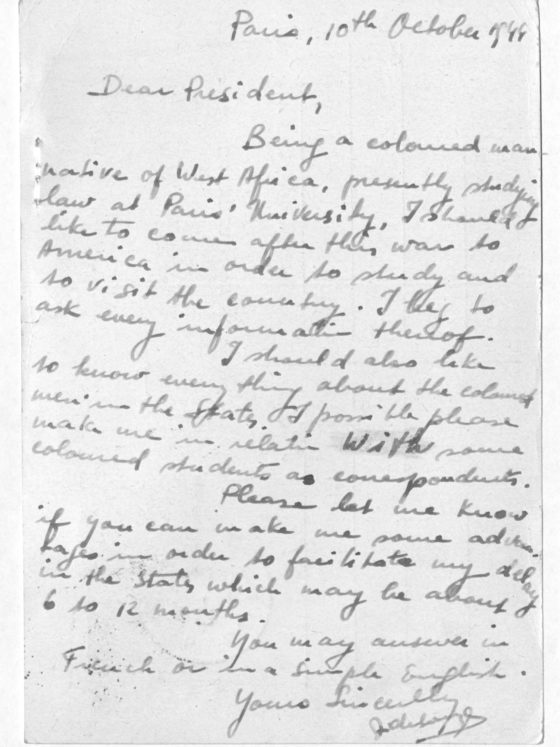

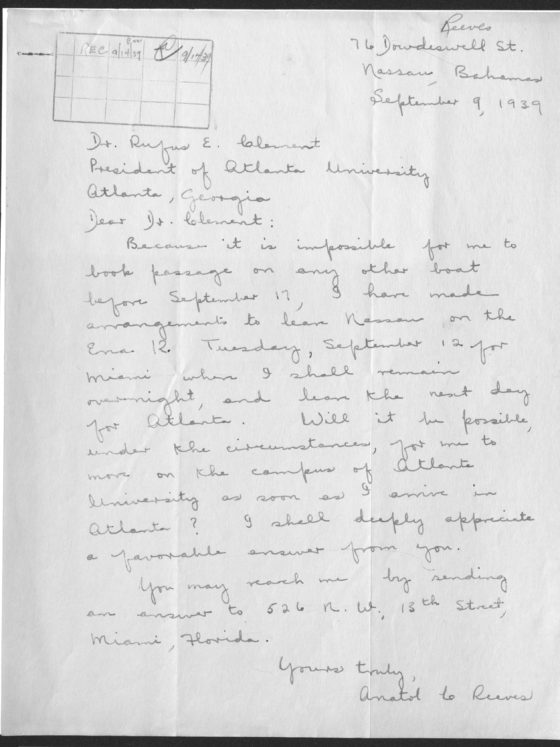

While under British rule, educational opportunities expanded in countries like Sierra Leone and Nigeria. In 1926 there were 18 secondary schools in Nigeria. That number expanded to approximately 100 by 1947, and over 700 by 1960, when Nigeria declared independence from the United Kingdom (Falola & Heaton, 2008). Despite this proliferation of European-style schools, Nigeria’s colonial government saw no need to expand education beyond primary and secondary schools, preferring to keep a portion of the population just educated enough for employment with the colonial government. Those who desired to attend a university had to seek education outside of the country. Nigerians began to attend university in London, but during the 1930s, an increasing number of Nigerian students began earning degrees at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) located in the United States. Nigeria’s first university, an extension of the University of London, wasn’t established until 1948, and didn’t become fully independent until 1962 (Falola & Heaton, 2008). The dearth of higher education options in Nigeria at this time is apparent by the number of letters from students seeking to study at Atlanta University addressed to then-president, Rufus Clement. Below you can see a sample of the correspondence sent to Atlanta University Center administration during this era.

Describe the impact colonialism had on the educational landscape for many African countries. Are there parallels when thinking about African American education and public schools? If so, explain.

For more research questions and additional sources, check out our LibGuide!

James Baldwin Correspondence, circa 1954

Harold Jackman Memorial Collection

AUC Woodruff Library

It is estimated that over 6 million Southern blacks left the agricultural South for the industrial North and Midwest in the 19th and 20th century. The blatant racial injustice of the South coupled with the North’s need for cheap labor led to what we now refer to as the Great Migration. Not only were African Americans of the South oppressed under the laws of Jim Crow but also from the mediocre economic opportunities in their rural areas. The possibility of better wages and an escape from the cruel discrimination they faced made a move out of the South even more appealing. However, many African Americans who left the South in hopes of a better life were met with violence and disdain. Numerous race- and labor- related riots occurred between the newly migrated black populations and white union workers, including the East Saint Louis Race Massacres which occurred in the summer of 1917 and resulted in the death of at least 39 African Americans.

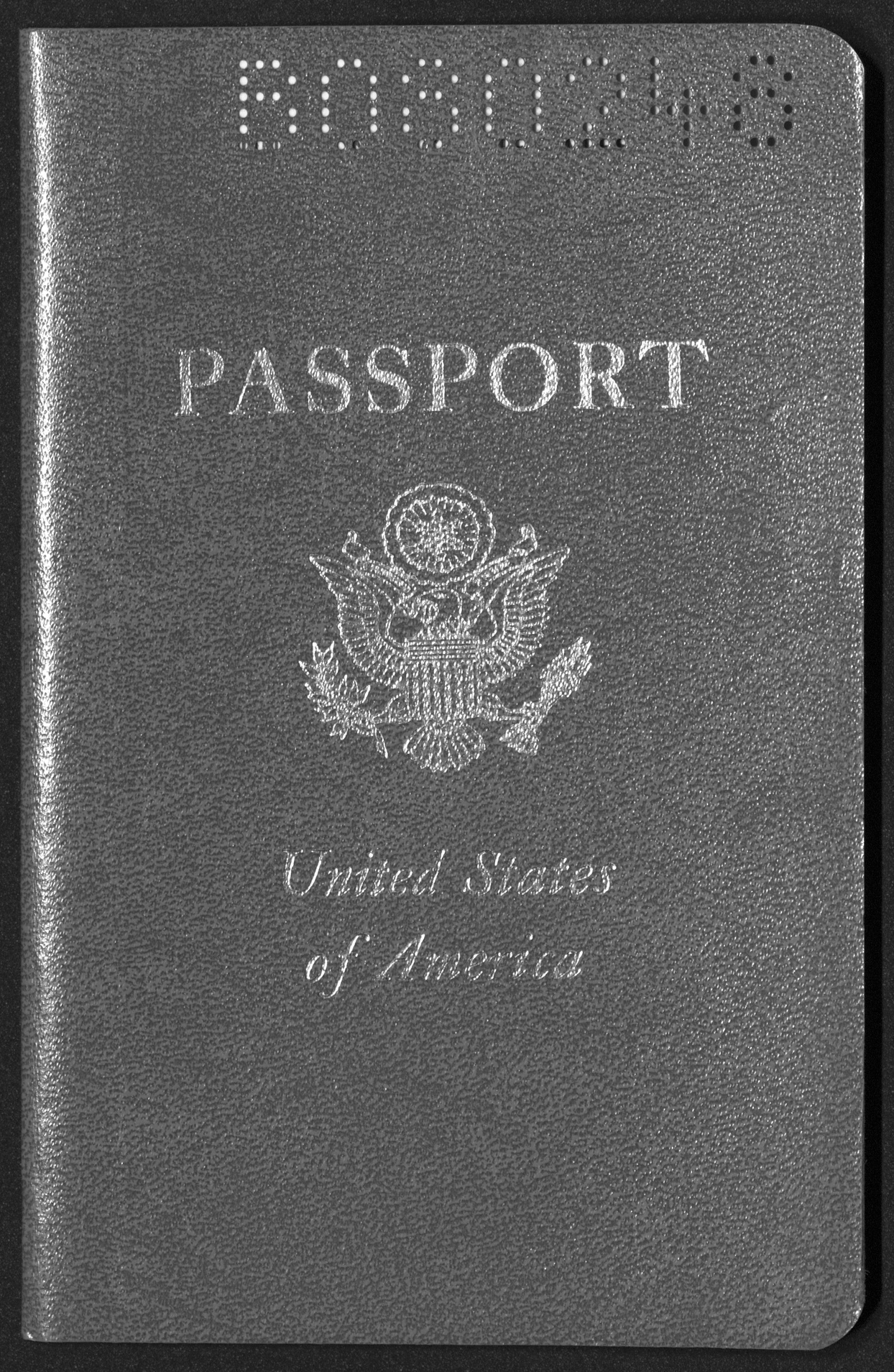

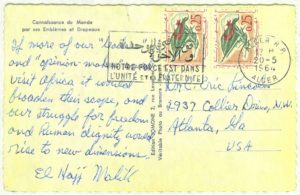

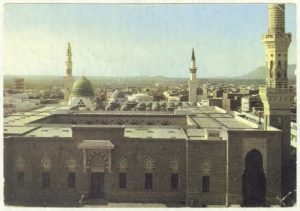

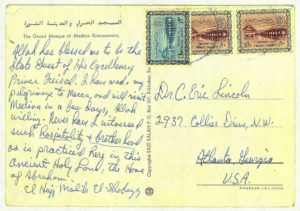

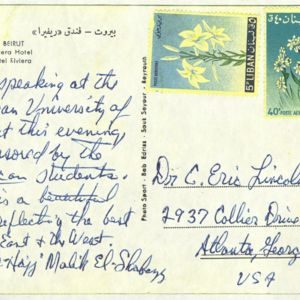

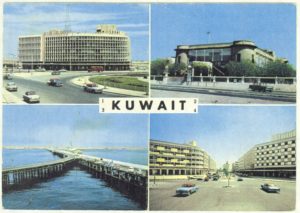

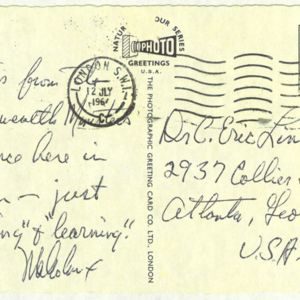

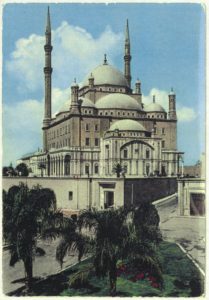

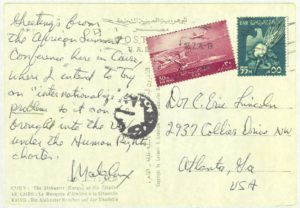

Racial tensions continued to be an issue for African Americans in the North and Midwest, and for a few, leaving the country altogether seemed to be the only way to experience the freedom they so desired. With stamped passports in hand, African Americans who left to travel abroad for temporary and permanent stays made sure to keep open lines of communication with their loved ones in the states. Some, like James Baldwin, chose to write letters and publish novels for American audiences about their experiences. Others sent postcards: Malcolm X wrote to C. Eric Lincoln, a leading African American scholar on the Black church and Black religion in the United States. But many simply chose to write of their encounters in personal travel journals, like James P. Brawley. Just as their choices of communication differed so did their reasons for travel. Brawley spent his time overseas during vacation, journaling about his everyday adventures. Religious zest prompted Malcom X’s journey to Mecca as well as Willis J. King’s missionary trips to Liberia. James Baldwin spent his time abroad writing one of his most renowned novels, Giovanni’s Room.

Playwright and novelist James Baldwin moved to Paris during the height of his career, in the midst of the Great Migration, to write numerous books and plays for the consumption of his American audiences. Though Baldwin had acquired fame, and many would assume fortune, based on his letters written to fellow playwright Owen Dodson he was still a struggling artist. In a letter to his friend, Baldwin confesses he borrowed against one of his advances for his upcoming book and would need to stay with Dodson while he was back in the United States. He also explained that he would only be able to travel once receiving his check from the book he was writing, a book that later became Giovanni’s Room. The lavish lifestyle that many would have assumed James Baldwin, a renowned author, would be living when he announced his move to Europe was the complete opposite of his reality. He had to deal with his own financial struggles while completing great literary works.

Malcolm X, also known as el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz, was a prominent African American leader and influential figure in the Nation of Islam who advocated for Black Nationalism rather than racial integration. Malcolm X traveled extensively throughout the country spreading this doctrine until his Pilgrimage to Mecca shifted his perspective on the separation of black and white Americans. In “The Autobiography of Malcolm X,” Malcolm X reflects on his time in the “Muslim world” and describes the letters he penned to dear friends and family members as well as a letter he sent to his assistants in Harlem to be duplicated and distributed to the press. In it he writes:

“America needs to understand Islam, because this is the one religion that erases from its society the race problem. Throughout my travels in the Muslim world, I have met, talked to, and even eaten with people who in America would have been considered ‘white’ – but the ‘white’ attitude was removed from their minds by the religion of Islam. I have never before seen sincere and true brotherhood practiced by all colors together, irrespective of their color.

“You may be shocked by these words coming from me. But on this pilgrimage, what I have seen, and experienced, has forced me to rearrange much of my thought-patterns previously held, and to toss aside some of my previous conclusions. This was not too difficult for me. Despite my firm convictions, I have always been a man who tries to face facts, and to accept the reality of life as new experience and new knowledge unfolds it. I have always kept an open mind, which is necessary to the flexibility that must go hand in hand with every form of intelligent search for truth.”

C. Eric Lincoln, who was a leading scholar on the Black Church and Black Religious studies in the United States, received numerous postcards from Malcolm X during his travels abroad in the People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and London. In one of the exhibited postcards below Malcolm X writes: “If more of our ‘leaders’ and ‘opinion-makers’ visit Africa it would broaden their scope, and our struggle for freedom and human dignity would rise to new dimensions.”

- What conditions in American living during this time period would encourage African Americans to travel abroad?

- Visit the AUC Archives Research Center to view The Autobiography of Malcolm X as told to Alex Haley and read the letter in its entirety.

- For more research questions and additional sources, check out our LibGuide!

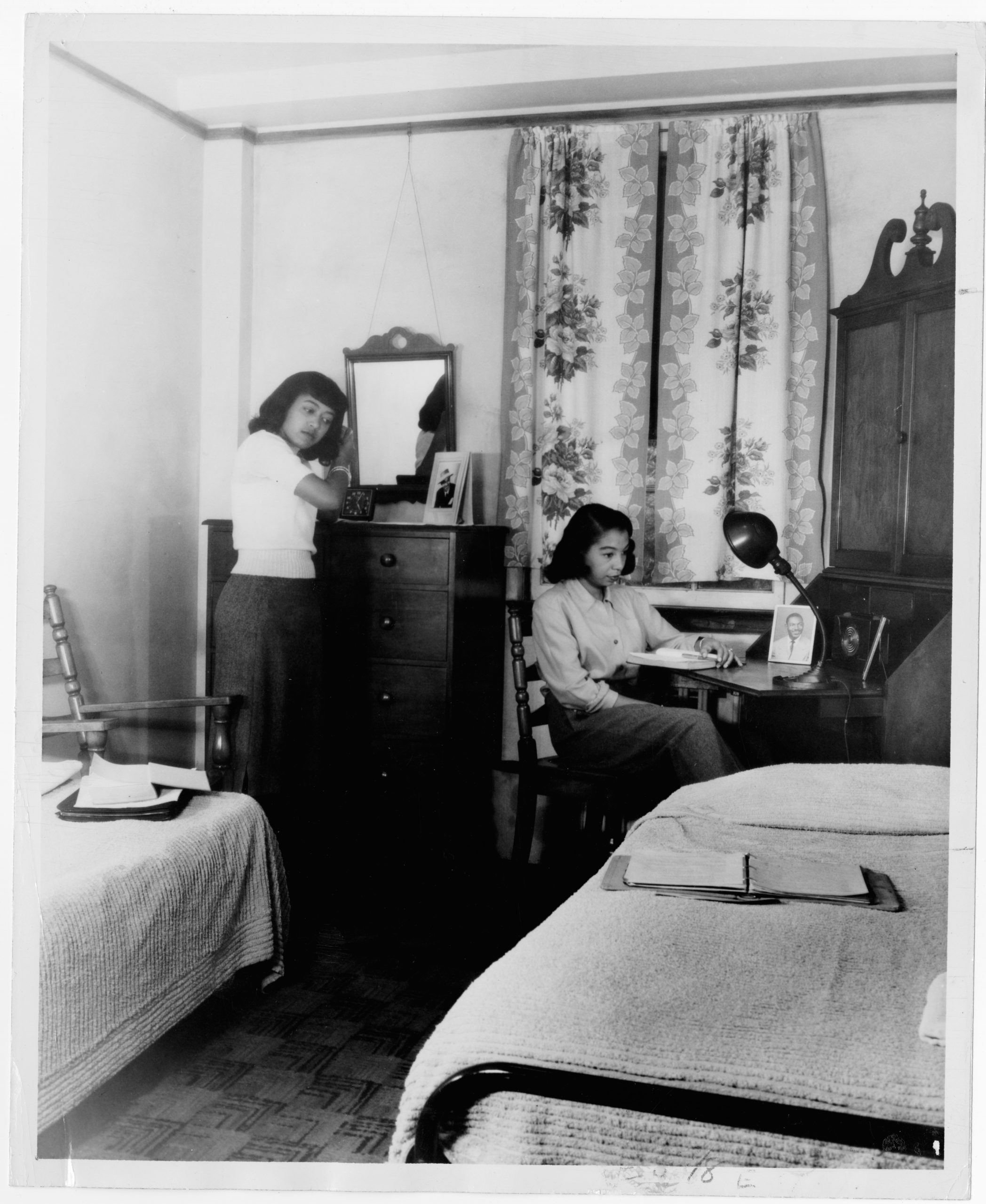

Atlanta University

Women’s Dormitory Interior, circa 1950

Atlanta University photographs

“Growing up in a world where black working-class and ‘po’folk,’ as well as the black well-to-do, were deeply concerned with the aesthetics of space, I learned to see freedom as always and intimately link to the issue of transforming space.”

– bell hooks, “Art on my Mind”

What do the ways we adorn our bodies or the walls of our home convey about our inner selves, dreams, and desires? How do the objects we collect and choose to display speak to our existence or lived experiences? And, as Alexander questions, “is there a particular power of the visual to make possible or imaginable that which is not the present reality?” The living room, as Alexander describes is the “not” space, it is “not the bedroom, or the bathroom, or the kitchen,” but rather a presentational or performative space within the private realm where one welcomes and entertain guests. This is the room where black imagination manifests itself through décor and objects on view.

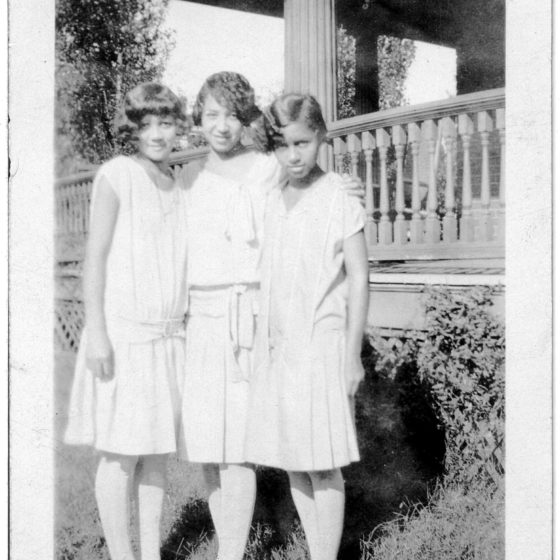

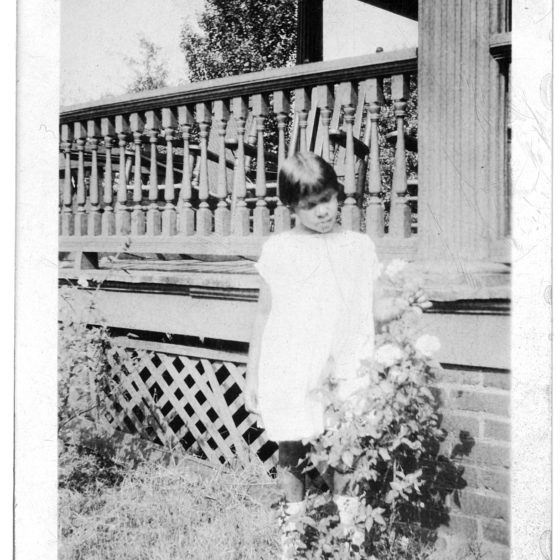

In the literal interior spaces of black people’s homes, Alexander states, “the self is made visible” through the conscious act of collecting and displaying objects affixed with personal memory and family history. This is made apparent in Henri Linton’s “Easy for One Hard for Two” (1965) as well as the photographs taken in Grace Towns Hamilton’s family home and the dorm rooms of Atlanta University students. The subjects in each painting and photo are positioned within their home, surrounded by items that reflect who they are and what they hold dear. Whether a humble one-room shack, a multi-level mansion, or a dorm room these dwellings are sites of transformative freedom housed with unbridled black imagination.

Frank W. Neal

“Oppression”, 1947

Oil on canvas

Clark Atlanta University Art Museum

In Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics, bell hooks reminisces on the times she spent in her grandmother’s home, learning how to “see” through the objects that shaped her childhood. She states:

This is the story of a house. It has been lived in by many people. Our grandmother, Baba, made this house living space. She was certain that the way we lived was shaped by objects, the way we looked at them, the way they were placed around us. She was certain that we were shaped by space. From her I learn about aesthetics, the yearning for beauty that she tells me is the predicament of heart that makes our passion real. A quiltmaker, she teaches me about color. Her house is a place where I am learning to look at things, where I am learning how to belong in space. In rooms full of objects, crowded with things, I am learning to recognize myself…She has taught me how to look at the world and see beauty. She has taught me “we must learn to see.”

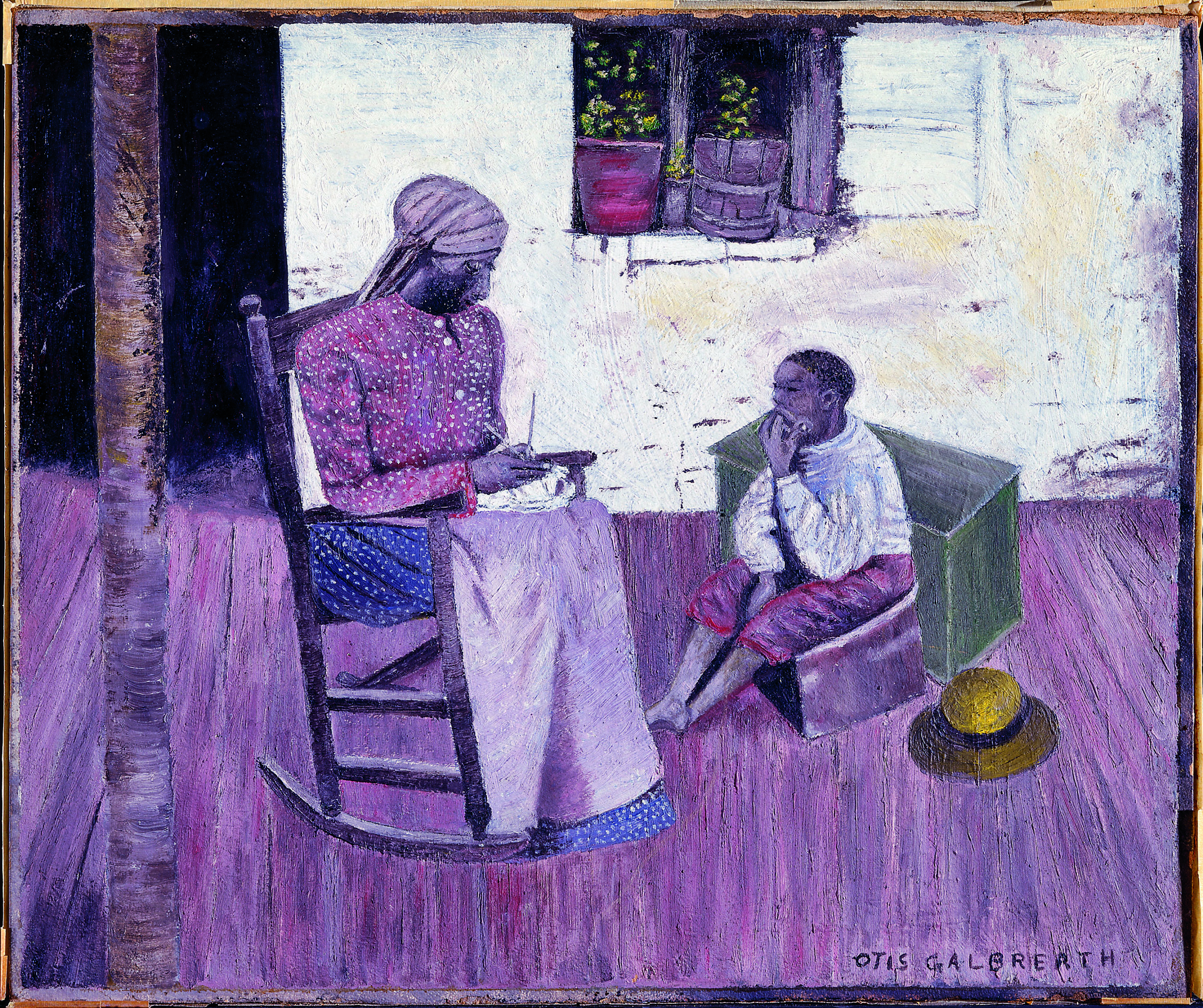

hooks learned to recognize herself by watching her grandmother move within the house she took care of and cared for. Frank Neal’s “Oppression” (1947) and Otis Galbreath’s “Let Bygones be Bygones” (1964), both illustrate the dynamics between performer and spectator in the private sphere hooks so poetically describes. The two paintings portray young boys observing older women, presumably the matriarchs of their family, in domestic spaces. Dressed in a long sleeve blouse and floor length skirt, the woman in Galbreath’s painting hunches over her needlepoint while a young boy, who sits across from her, intently watches her movements, just as the young boy in Neal’s painting studies his mother’s down casted face. Both women seem to either not notice or not care that they are under the watchful eyes of their young ones and continue to perform the daily labors of homemaker.

The titles of both paintings allude to the mental and emotional stress endured by those in marginalized communities, yet one image depicts a somber moment of succumbing to the pressures of the world while the other illustrates the necessity of letting go of past grievances to focus on current concerns.

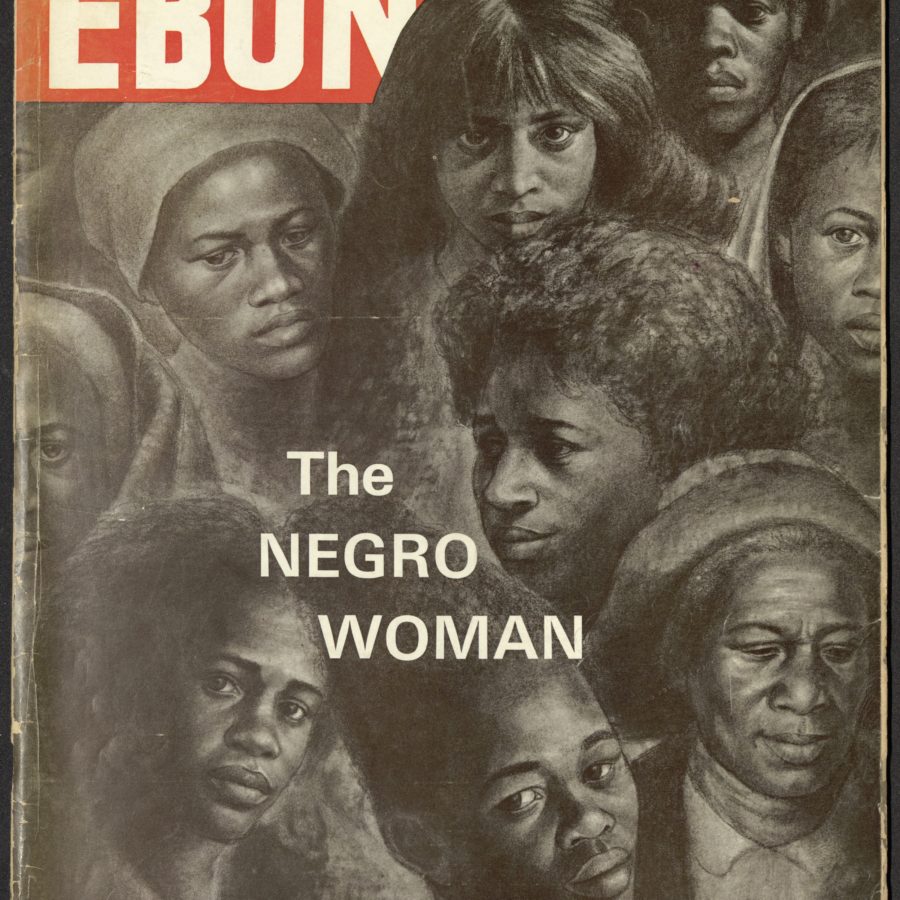

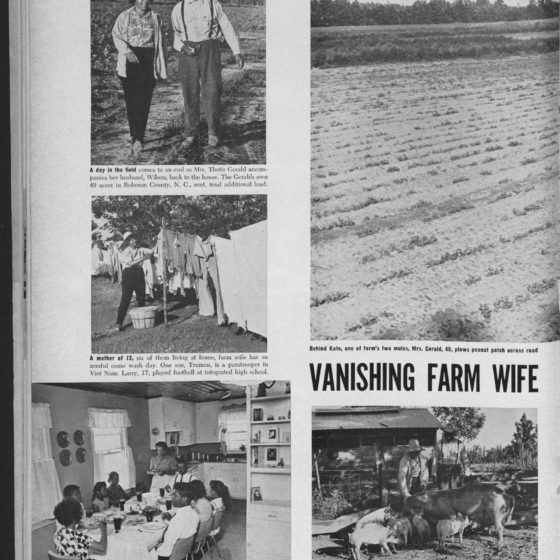

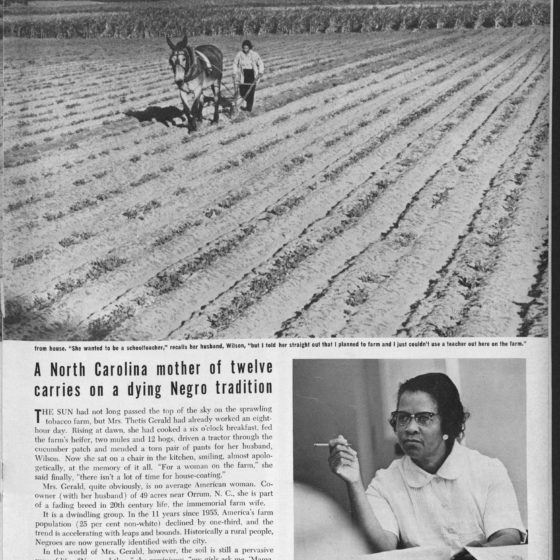

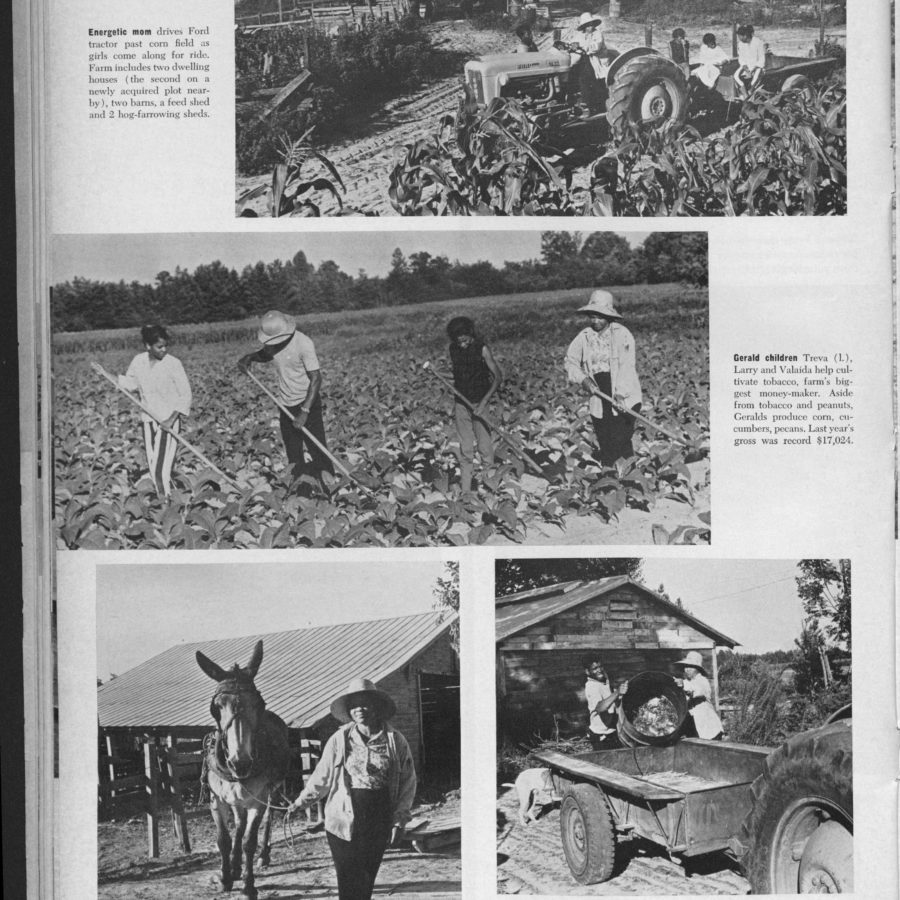

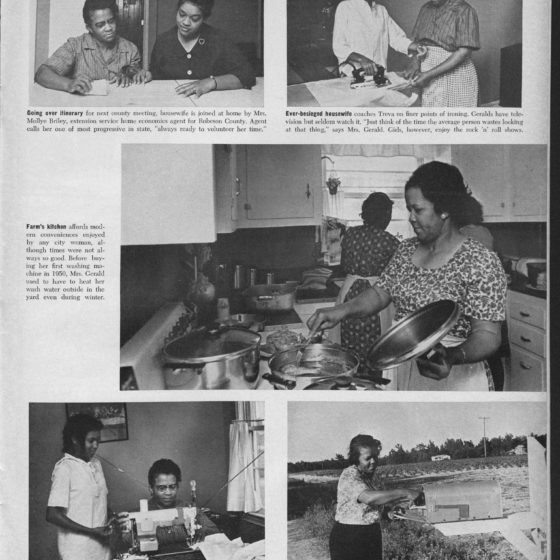

African American women have been fixtures within the American domestic sphere. They have been expected to maintain and upkeep their own homes as well as others. From enslaved African American women who were regulated to working in the “big house,” mammies, and wet-nurses to (often under-) paid maids, domestic workers, and nannies, these women carried much of the emotional burden of caretaker and homemaker. Women such as Elizabeth “Lizzie” McDuffie, who worked as a White House maid from the 1920’s until the 1940’s and wrote of her experiences in her unpublished memoir “The Back Door of the White House.” Or, others, like Mrs. Thetis Gerald, a North Carolina “Farm wife,” who “cooked a six o’clock breakfast, fed the farm’s heifer, two mules and 12 hogs, driven a tractor, through the cucumber patch and mended a torn pair of pants for her husband, Wilson” every morning.

In addition to cooking, cleaning, tending to the farm and mending her family’s clothes, Mrs. Gerald also was a co-chairman of the state’s Home Demonstration Council, a Department of Agriculture federal extension program. The national and local Home Demonstration Councils, established during the early twentieth century, offered practical demonstrations in home economics and agriculture. The demonstrations taught women farmers updated methods for accomplishing their household obligations and encouraged them to improve their families’ living conditions through home improvements and labor-saving devices.

Click on the arrows in the viewer to page through the booklet or expand to full screen to see a larger version.

“The future history of America will be shaped in large measure by the character of its home life. AS IS THE HOME, SO IS THE COMMUNITY AND NATION.”

- What role did women play in the making of a home and attempts to obtain the American Dream?

- To learn more on Home Demonstration Programs specifically directed towards African Americans in Georgia, read Lilian Camilla Weems 1956 thesis entitled, “A Study of the Negro Home Demonstration Program in Georgia, 1923-1955.”

- For more research questions and additional sources, check out our LibGuide!

Maynard Jackson

“Take a Minute, Save a Child”, circa 1981

Maynard Jackson mayoral administrative records

AUC Woodruff Library

“The inescapable and irreducible danger of being a black man or woman in this country is being forced to live with so vast a horror, day in and day out, that one finally ceases to be able to react to it.”

James Baldwin, “The Evidence of Things Not Seen”

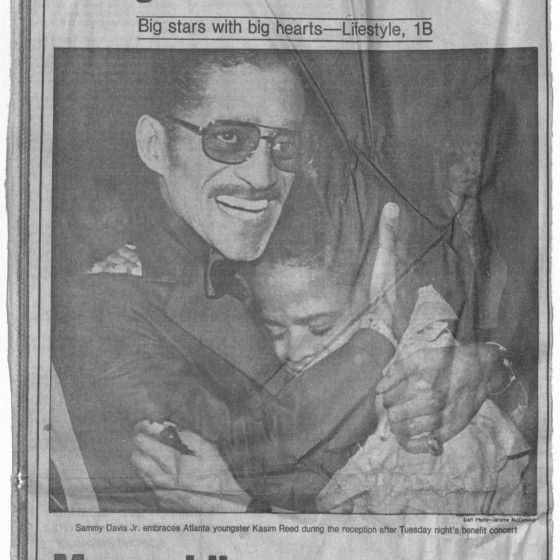

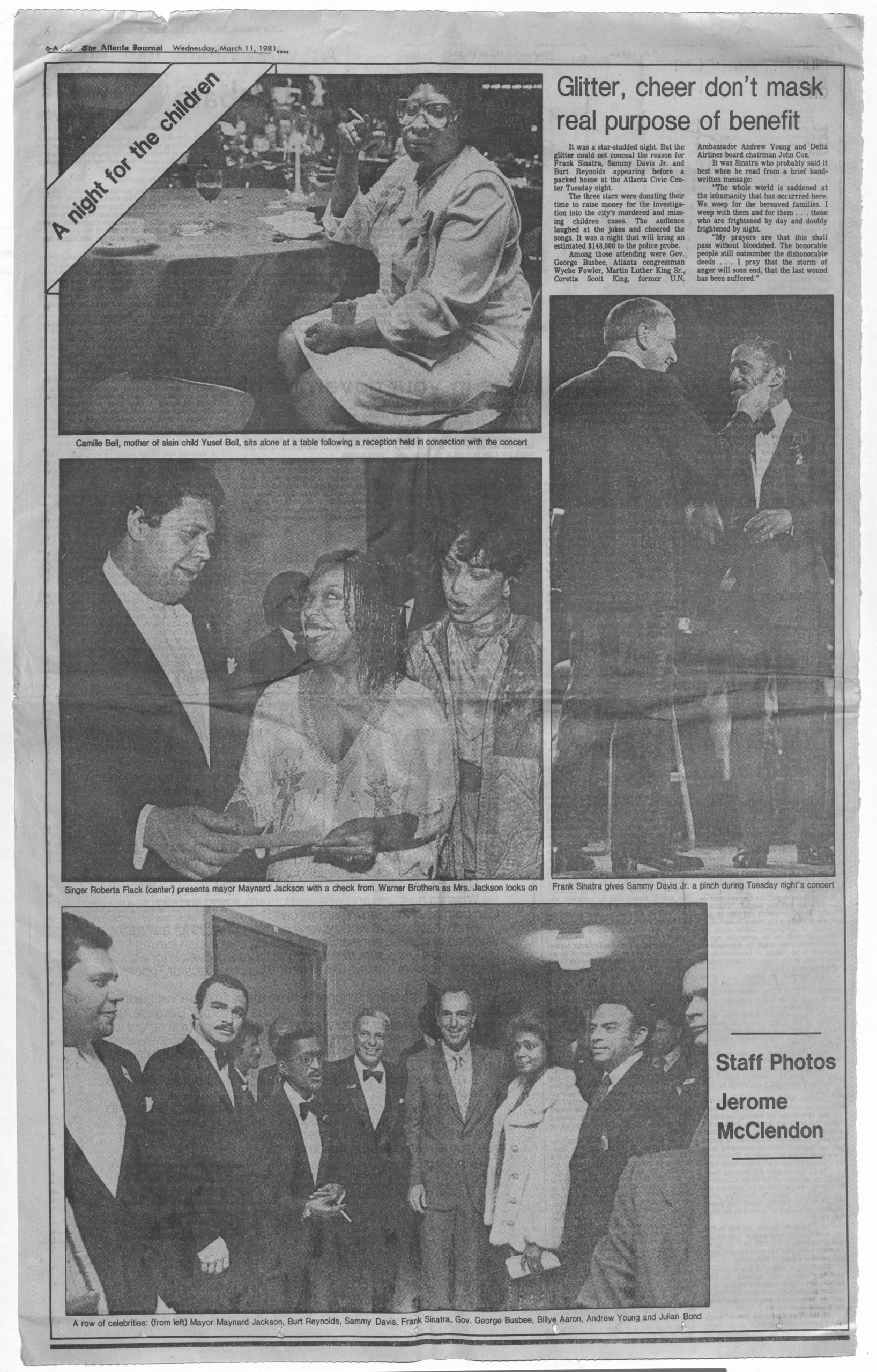

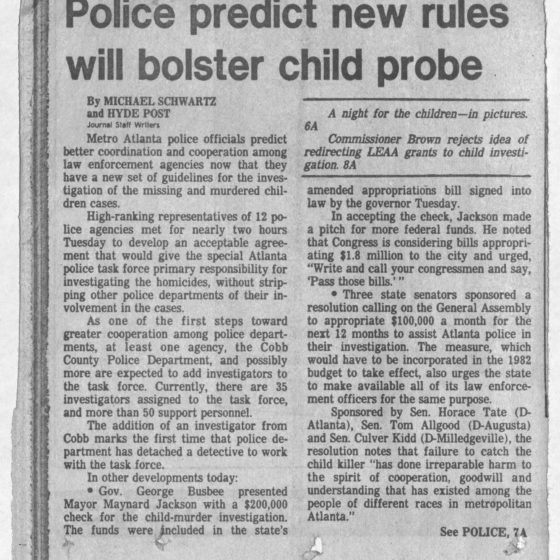

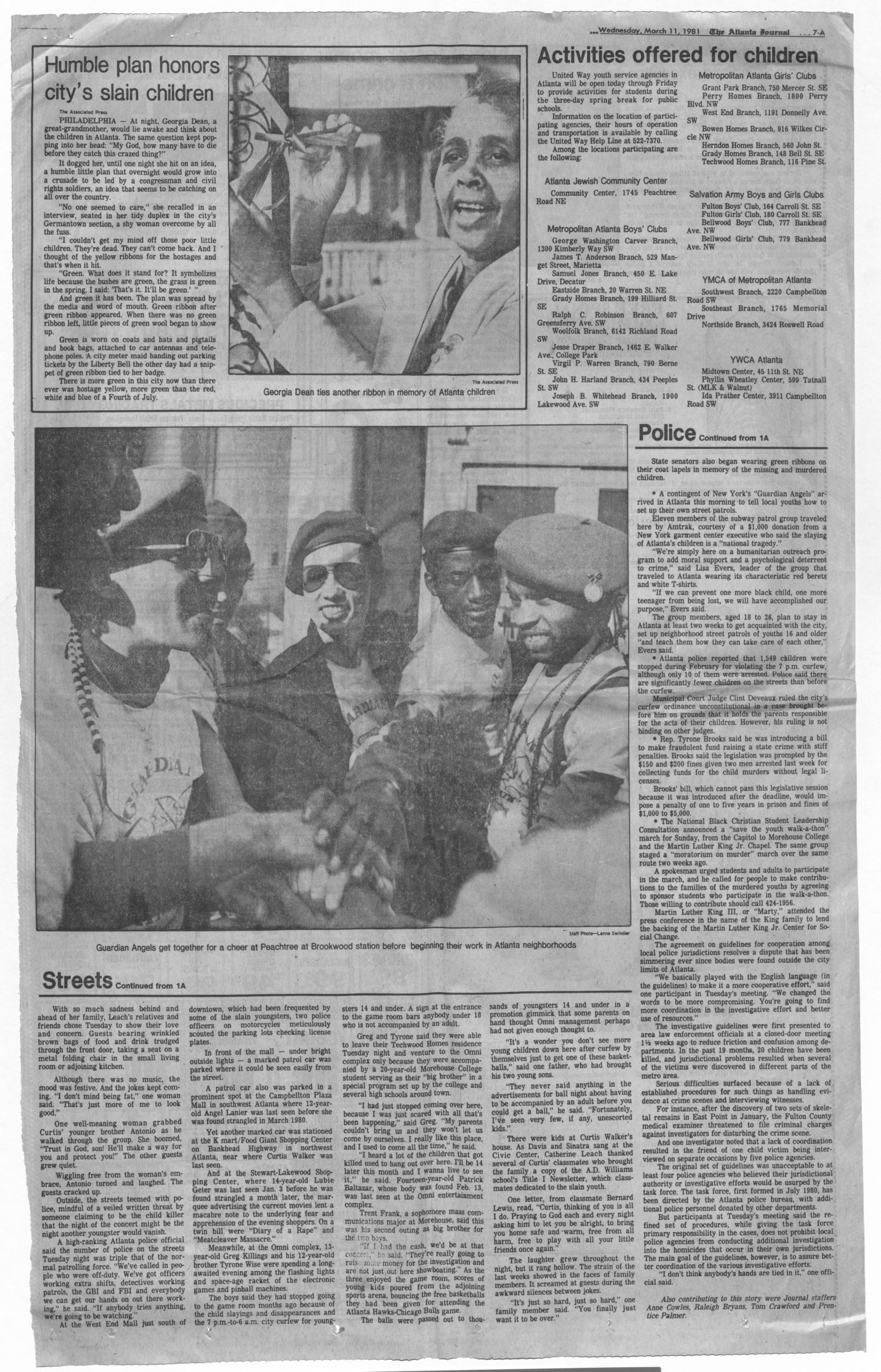

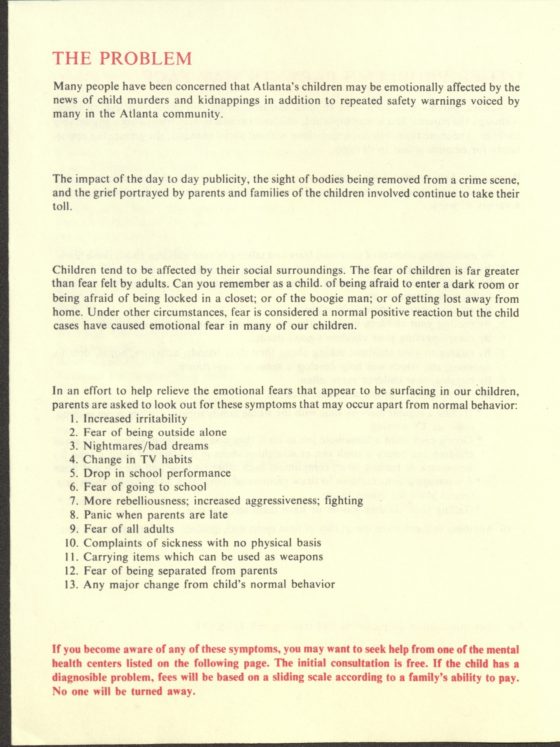

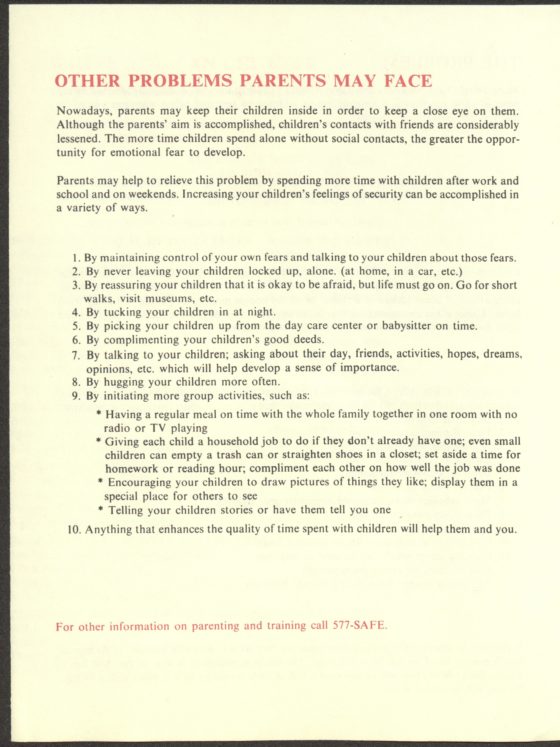

The home, for many, is a place of serenity or site of refuge from the uncertainties of the outside world. It is a place we can be free and feel safe. However, what happens when fear takes ahold of a community and danger doesn’t just come to your door but rams through it? African Americans have dealt with such concerns related to the safety of their family in and around their homes for centuries. In his 1981 Playboy article, “The Evidence of Things Not Seen,” James Baldwin describes the paralysis-inducing terror of being a black person in America while referencing the Atlanta Child Murders of 1979-81. During this time, a string of kidnappings and murders occurred in the city of Atlanta, resulting in at least 29 African-American children, teens, and young adults (mostly boys, all from lower socioeconomic backgrounds) reported missing or murdered. While the city as a whole was stricken with panic, black Atlantans, who were the targets of the attacks, bore the brunt of the devastation and felt the most neglected. The Atlanta Police Department was accused of not pursuing serious leads or possible connections between the murders and disappearances until almost a year after the first bodies were found, leaving the families and friends of the victims living in the “city too busy to hate” wondering if the city was actually too busy to care.

Community-led search efforts and “bat brigade” were formed to offer assistance in finding the missing children and protecting the housing projects that many of the boys were taken from. One news article entitled “Atlanta Volunteers to Begin Police-Backed Patrol Duties” states:

“Some 200 volunteers armed only with green and white baseball caps, photo identification cards and walkie-talkies are expected to be on the streets Monday as police-sanctioned citizens’ patrols watching over neighborhoods shaken by the mysterious deaths of 23 youngsters and disappearances of two others in the last 20 months.”

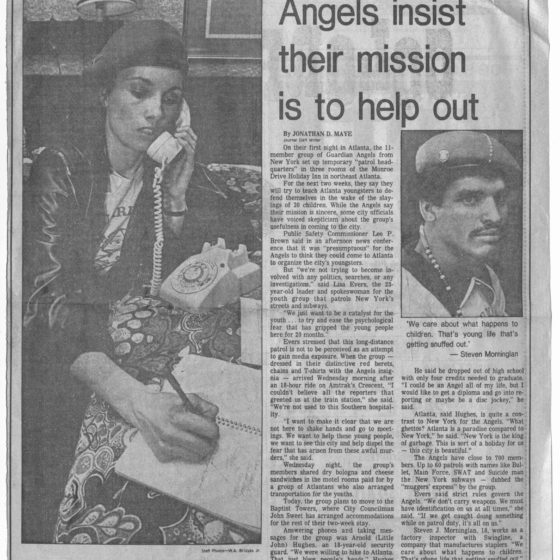

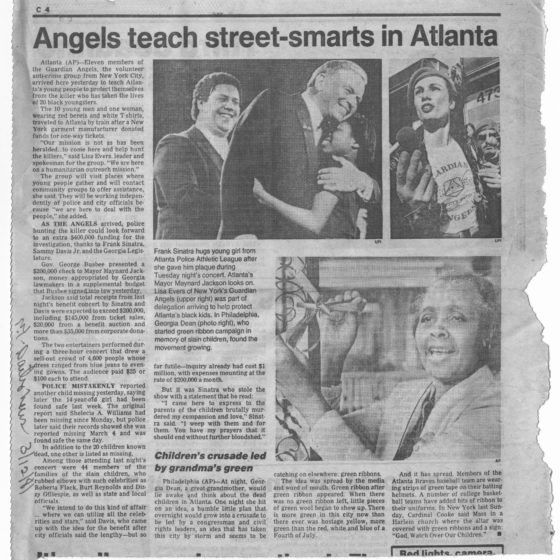

National and international volunteer organizations like the Guardian Angels, a non-profit, New York City based crime-prevention group, came to Atlanta to voice their condolences and offer self-dense classes.

Lisa Evers, a 23 year old Guardian Angels leader and spokeswoman, shared her thoughts:

“We just want to be a catalyst for the youth…to try and ease the psychological fear that has gripped the young people here for 20 months.”

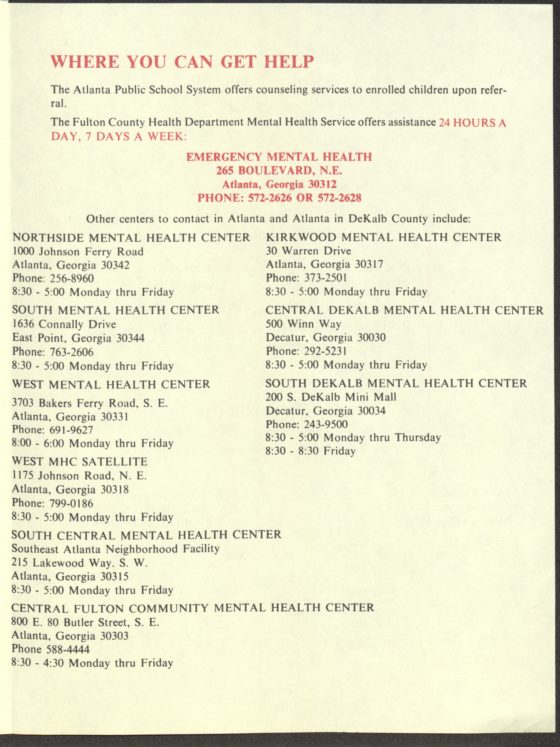

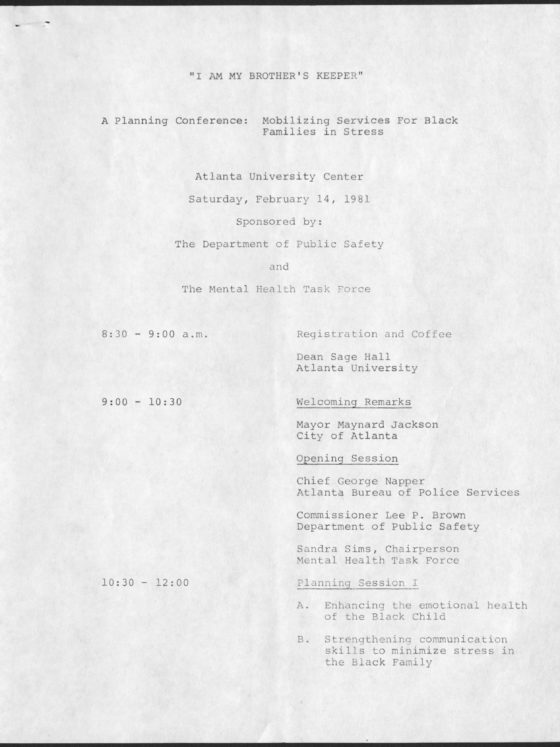

Official task forces and grassroots organizing brought together both government officials as well as community leaders to form committees to address concerns relating to the physical safety and mental well-being of those most affected. The Committee to Stop Children Murders, chaired by Camille Bell (mother of murder victim Yusuf Bell), laid out several of their intentions in a 1981 letter, which included addressing potential violators of children rights, counseling families affected by tragedy, and working to prevent the physical, emotional, moral or educational destruction of children nationwide. Black Atlantans mobilized together to create and provide resources to counteract both the immediate and long term effects of the reign of terror afflicted on the city. Workshops and conferences such as “I Am My Brother’s Keeper,” held at the Atlanta University Center, sought to both identify signs and symptoms of stress in young black children as well as train parents, teachers, and social workers on how to effectively work through their trauma.

Although the effects of Atlanta’s missing and murdered children are still felt today, it is evident that great community efforts went into protecting the neighborhoods, homes, and spaces they occupied. Collectively they did not cease to react but sought to rebuild and re-envision a place of their own even in the face of “irreducible danger.”

Oscar Harris

“The House: The Wildflower”, circa 1991

Oscar Harris collection

AUC Woodruff Library

Oscar Harris, a renowned architect and artist, kept record of the construction progress of the Atlanta home he both designed and has lived in since 1991:

“The Wildflower (House) is now about 80% complete. It is looking good…When I first started the design of the house I did a lot of sketches in a black book similar to this one titled “The Wildflower” The House – I have [lost] that book…I hope to find it but until then I will continue my thoughts in this book.”

Harris, like many represented within this exhibit, envisioned a space that was not yet apparent and created a place that was distinctively their own. The homeplace, whether in its metaphysical understanding or physical construct, is a site for creative freedom and liberation.

Even when the troubles of the world creep into the far corners of the home or dark recesses of the mind, the private interior (in reference to place or self) allows for intimate moments of solitude, contemplation, and self-affirmation. Here, the black body is sovereign over the space it occupies and designates as its own. It is within the constructed boundaries of the physical home that the self is granted space to be free, real, and complex.

Click on the arrows in the viewer to page through the booklet or expand to full screen to see a larger version.